This is an archived material originally posted on sciy.org which is no longer active. The title, content, author, date of posting shown below, all are as per the sciy.org records

Is Piracy Really Killing the Music Industry?

Originally posted on sciy.org by Ron Anastasia on Tue 06 Mar 2007 11:11 PM PST

I stumbled upon this remarkable website a few weeks ago and have become a regular reader. Its author, Daniel Eran, imo is one of the most informed observers of the computer and digital entertainment industry, especially the ongoing battle between Microsoft, Linux and Apple. Highly recommended. ~ ron

RoughlyDrafted Magazine: Tech Q1 2007

Is Piracy Really Killing the Music Industry?

© 2007 by Daniel Eran

Wednesday, March 7, 2007

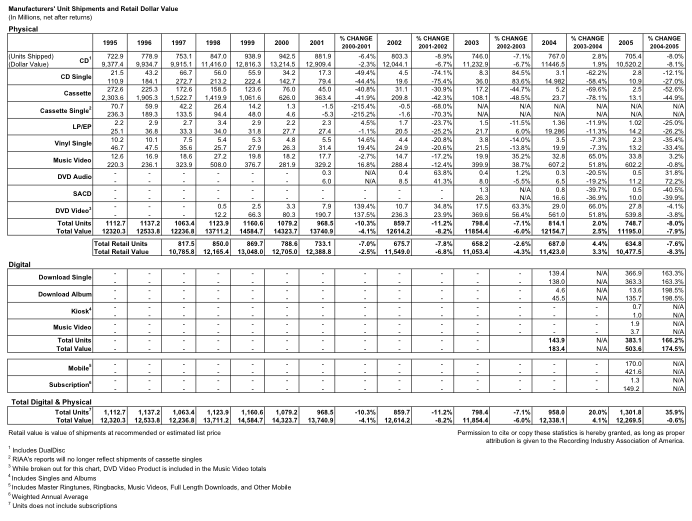

Various music industry trade groups claim that piracy is killing their industry, and are suing file traders and the sites they use. Are music sales, revenue, and profits down? Are MP3 downloads preventing music sales or do they instead help advertise new music? Are paid music downloads profitable or are they still insignificant?

RoughlyDrafted Magazine: Tech Q1 2007

Is Piracy Really Killing the Music Industry?

© 2007 by Daniel Eran

Wednesday, March 7, 2007

Various music industry trade groups claim that piracy is killing their industry, and are suing file traders and the sites they use. Are music sales, revenue, and profits down? Are MP3 downloads preventing music sales or do they instead help advertise new music? Are paid music downloads profitable or are they still insignificant?

Let's Ask the RIAA

Unsurprisingly,

the music industry's own research and opinions on the subject support

the idea that unauthorized distribution of music is killing both sales

growth and profits. The result: music costs more to produce, there's

greater risk in signing smaller acts with uncertain audiences, and the

lower sales volumes have forced the labels to raise the retail price of

CDs.

From the label's perspectives, the only solutions are to:

-

•lock down music so users can't share the copies they buy

-

•prosecute file traders and win settlements against them to discourage the practice

-

•institute market pricing for music, so buyers pay more for popular music and less for back catalog music

Isn’t The Customer Always Right?

The RIAA has its critics, many of whom are music customers. Among them are:

-

•the free and open source software crowd, who like the idea of freely shared content

-

•people who don't want to pay for things that can be found for free, and don't like being sued

-

•people who don't want to be restricted in their use of purchased music

-

•companies who don't benefit from the market pricing of music

Before

looking at the merits of the RIAA’s complaints and examining their own

data on sales, take a look at the rational presented by its various

circles of critics, and see whose perspective best fits the facts.

Free as in Beer, Speech

Among

the most effusive and articulate of critics are the minds who make up

the volunteer collective of free and open source software. These people

have spent a lot of time thinking about the nature of shared ideas and

intellectual property, and some try to apply the principles proven to

work in delivering shared, open code into the world of entertainment.

The

difference, of course, is that free and open source software is written

by volunteers. GNU/Linux, BSD, and other projects' code can be shared

as desired by their creators.

The GPL and BSD style licenses

seek to enforce different schools of thought on how content should be

shared. However, neither can be applied to the commercial music

represented by the labels, because none of that music is free or open.

Britney

Spears' music is just as closed and proprietary as Microsoft Windows,

and nobody has rights to distribute it under a free license, just as

Microsoft has no rights to distribute Linux code without following the

license provisions of the GPL.

Reasonable

proponents of free and open content don't confuse unauthorized use of

commercial music with "free content," and have instead sought to create

their own music, movies and other entertainment, and share them under

agreements like the Creative Commons licenses.

In

their ideal world, there would be no DRM, no or at least few middleman

labels selling their representation and marketing, and musicians and

other performers would be supported by user donations, sponsoring

companies, or perhaps sunshine and love.

Think of the Children

While

many free and open source software proponents are intelligent,

experienced, and affluent, there is an epidemic of poor and stupid

people around the world. Many of them have been quarantined into higher

education campuses in a social engineering experiment to educate them

and make them valuable to society.

All

that exposure to education and liberal thinking--considering facts and

being willing to change their outlook based upon that new

information--frequently results in more free and open source software

proponents, with less attraction to music from Britney Spears and a

greater interest in the work of smaller indie artists.

Along

the way however, the problems of being poor and stupid commonly result

in run-ins with authority. The RIAA is increasingly becoming a prime

example of this; it has been targeting the poor and stupid to create

fear, uncertainty, and doubt about the safety of trading files.

The

RIAA mounted its legal attack just as sales of music to younger

demographics appeared to collapsed in tandem with Internet file

trading. However, things are not always as they appear, as the numbers

indicate later.

The Scarcity Behind Supply and Demand

In

trying to emulate their smarter and more experienced role models, the

poor and stupid have tried to create economic arguments against the

commercial existence of music.

A recent popular meme is to describe music as a "non-scarce good"

and DRM as an artificial construct designed to convert music into a

scarce good, one that can command a high price. This argument is absurd.

Music

itself--as well as movies and other forms of entertaining,

intellectual, and artistic performances--is most certainly a scarce

good. It costs many thousands of dollars to produce an album, and

millions to create movies.

That expense, related to not only the "above the line" performers, but also the "below the line"

technicians involved in production, and expenses in advertising,

promoting, and the various administrative costs, all make music and

other productions very expensive projects. Expensive things are scarce.

If the resources to produce music were not scarce, there would be no American Idol or Star Search,

and the planet would have 6 billion rock stars. Music is a scarce good.

The fact that it can be mass duplicated after production finishes does

not make it a non-scarce good. There are lots of ideas with clear and

obvious value that are not tangible nor consumed:

-

•Currency is artificially scarce. Anti-counterfeiting measures are essentially a “DRM,†protecting the value of currency and propping up the economy.

-

•Apartment rentals invent artificial scarcity to exchange privacy for money. A landlord could shove a dozen other people in your apartment. By not sharing your space, value is created and rent rises.

-

•Consulting work is similarly based on the scarcity of an expert's time. If time and space knew no boundaries, we could all be experts in every field and solve each other’s problems for free.

Time

and space are constrained however, as are raw materials, talent, and

good ideas. All those constraints result in scarcity, which demands

effort and expense to collect, expend, or consume. We vote on how to

distribute scarce things with our money.

Counterfeiting vs Piracy

Arguments

that “ideas†like music have no value because they can be duplicated

are as fallacious as suggesting that a copy machine creates value when

it counterfeits money. No, it doesn't.

Fraud

might temporarily enrich the counterfeiter, but it steals from everyone

else who has worked for their money, because a fraudulent supply of

money devalues real money.

Counterfeiting

is such a threat to the worlds' economies that governments enact harsh

punishments for counterfeiters, invest in developing

anti-counterfeiting methods, and carefully police their money supplies.

It

is therefore no surprise that unauthorized copying of music is

similarly viewed as a serious threat by those who benefit from a tight

hold on its supply, or that they are interested in DRM as a mechanism

of preventing copying, or that they are work to create strong copyright

laws, penalties for evading the law, and are suing those who do.

The

main difference between money counterfeiting and music piracy is that

nobody benefits from counterfeiting apart from the counterfeiter, while

more people benefit from freely duplicated music: pirated music doesn't

only eat into music sales, it can also act as an advertisement and

promotional tool.

Record

companies have long played their music on the radio for free, something

that has no analog in the comparison to counterfeit money. The real

question is: to what extent does file sharing hurt or help the industry?

The Real Customers

Neither

the free and open source software people--who aren't interested in

commercial music--nor the poor and stupid--who don't want to pay for

music at all--are ideal customers. The real customers are people who

buy music. They buy millions of CDs every year, and an increasing

number are buying song downloads online.

This

pool of people make up the sweet spot. Record labels take them for

granted, and focus most of their efforts on trying to herd people from

the first two groups into this population, using threats of lawsuits

and other forms of intimidation, including the use of often excessive

DRM aimed to force paying users from ever leaving the pool and joining

those who don't pay for what they want.

Carrots vs Sticks

People

respond better to positive, welcoming carrots than the stick of a

police crackdown. Give an employee a critical summary of their

screw-ups, and they will immediately stop listening to everything you

say and consider you a bad manager. Highlight what they do well, and

they will turn themselves inside out to please you.

The

same principle applies everywhere else humans exist. Send police into a

poor, crime ridden neighborhood to "control crime" and the crime will

continue, and probably increase. Provide education and create

opportunities, and those same people will clean up their own

neighborhood.

America's

wars on Terror, Drugs, and Science have not resulted in victories, only

in huge prison populations that cross-train fiercer criminals and in

publicity campaigns than only appeal to those who designed them. If the

US would dial back into its recent history, it could discover that

investing in education and creating opportunities for advancement would

solve its problems with much less spending and far better results.

Similarly,

if the record labels really want to expand their pool of paying

customers, they need to focus on creating sales instead of attacking

the poor and stupid who are unlikely to pay for their product anyway.

The labels are so afraid of change that they failed to recognize the potential for digital music sales a decade ago, and have more recently dragged their feet in getting behind sales of music downloads.

Companies Against the Market Pricing of Music

The

forth group critical of the music label's policies also represents a

huge part of the solution to the music industry’s problems.

That

group includes Apple, which makes very little money in selling music in

its online iTunes Store. Increasing the price of music is not in

Apple's interests at all, because the company is primarily hoping to

ensure a supply of music for its players.

Of

course, Apple is also interested in expanding the supply of music sold

through its online store. This both brings attention to its hardware

sales, as well as enabling the company to expand its sales into TV and

movie programming. Obviously, the more music that Apple sells, the more

revenues the labels will earn.

Apple

is the carrot that music labels can use to reward customers for buying

their music: offering a wider selection of artists and a deeper catalog

to encourage more sales. As people discover more music they like, they

will in turn buy more music.

Alternatives

to iTunes have failed primarily because instead of handing out an

attractive carrot, they threatened users with a fearsome DRM-armored

stick. MiniDisc and DAT were so encumbered by restrictions that they negated their own benefits.

Microsoft's PlaysForSure and Sony's ATRAC

similarly applied layers of DRM to suit the needs of producers so

egregiously that consumers were left with little reason to buy their

products.

What Do the Facts Support?

Do

the facts indicate that the labels' lawsuits, DRM, and market pricing

strategies are effective? Are the assumptions that music sales,

revenue, and profits are down accurate? Does file trading preventing

music sales or does it instead help sell new music? Are paid music

downloads profitable or are they still insignificant?

Take

a look at figures reported by the RIAA itself. One warning sign: The

RIAA contrasts "physical sales," the vast majority of which are CDs,

with "digital sales," by which it intends to mean “music downloads.†It

is somewhat scary that the RIAA in 2007 is not aware that CDs are

digital music.