Contemplative Studies is a recent field that endorses first person and third person views in academic discourse. Hence it encourages “scholar-practitioners.” The first person aspect is encouraged but not always necessary as personal practice. However even if one is not a practitioner of the field one studies and discusses, the attitude should not be one of purely objective and etic observation and analysis but of a relational knowledge that includes subjective engagement and reflection at the level of the experience. In either case the subjectivity is involved along with objectivity at the level of contemplative experience. For this one needs a critical subjectivity. To be a “scholar practitioner” implies this division of experiencing subject into the experiencer and observer and from the observer to the communicator. The subject is the experiencer and the object is the experience on one side and the language community on the other. Between the subject and its objects is a range of relations between subjective and objective knowledge. At the far end of the subject is the experience of the subject. This experience is irreducible and cannot be observed or communicated in its essence. This is known as the hard problem of consciousness. It is of the nature of the knowledge that we have of our self-existence; it is self-evident knowledge and is a difference in kind from reflexive knowledge, which is observable and describable. At the other end is objective knowledge. Science has tried to stipulate the basis of universal objective knowledge as that which is measurable using universally agreed upon measurement standards and communicable using universally agreed upon conventions of logic in a universally agreed upon denotative language. A denotative language is one in which words have fixed and clear meanings. Contemplative Studies does not reject this kind of knowledge. It may be called exclusive third-person knowledge. Between this and the inexpressible experiential knowledge of the subject, there are grades of subjective objectivity which mix first person and third person knowledge. At the end closest to the experience of the subject is poetry, which operates at the intersection between inexpressible experience and the categories of understanding. It’s language use is connotative, which means that words are fuzzy and have allusions based on context which communicate feelings, sensations, perceptions and moods (affect) that go beyond the fixed meanings of denotative universal language. They are not objective in the same way as scientific language but they also aim at universality through subjective precision. Much contemplative literature is of this kind. It may be poetic or it may challenge denotative language through puzzles, paradoxes, parables and analogies. Our first person accounts of contemplative states may also take this expression. Contemplative Studies accepts this kind of expression among its various forms of source material. At a first person level this can include expressions of active imagination (consider Jung’s Red Book or Black Books), journaling. introspection or varieties of what the American psychologist William James called “radical empiricism.” One recent methodology for bridging first person subjective experiences or accounts and objective knowledge that has arisen in the academy is neurophenomenology.

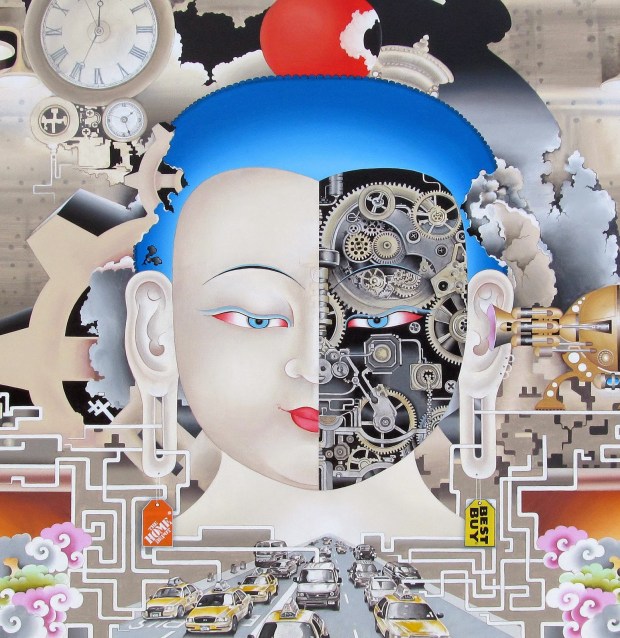

More usually, mediating between subjective expression using connotative language and objective expression of denotative language are frameworks that may be cultural, religious, metaphysical or ideological. These frameworks formalize vocabularies and assumptions that are understandable to a language community as forms of convention. These forms of convention constitute degrees of closure and degrees of porosity. Contemplative literature, even one’s own contemplative expressions, however poetic, is framed by one or more of these conventions, often unconsciously. This is why critical subjectivity of first person expressions must include autoethnography and auto-hermeneutics. How did we enter into a contemplative domain? Contemplative traditions, practices and experiences come to us in the postmodern global world often like commodities in a supermarket, without any acknowledgement of their origins and the distances they travel or the hands they pass through. The marks of colonization and capital are everywhere around us, however much care is taken to erase them. On the other side, non-Western nations have often accepted to stereotype themselves nationally or regionally through Orientalisms. Beyond this our languages have their own histories of power dynamics and cult closures. At the same time, there is the fragrance of long traditions, of ancient histories passing experiences in communities through varied cultural forms, oral, written and performed, that grow in density and become culturally normalized over time. And there is the beauty of rebirth, of experiences that offer themselves under new conditions after having vanished for centuries. The autoethnography of the scholar practitioner of Contemplative Studies needs to be both emic and etic. An emic account understands and expresses experience in terms of the inner realities of language communities who have made these experiences into their tradition. Their behaviors code for a context which is often hidden and needs “thick description.” On the other hand, to look at oneself “from the outside,” in an etic account, is also necessary to deconstruct the closures and assumptions of sectarian histories and allow translations across borders. In an autoethnography which aims at a future of convergent pluralism, we have to become conscious of the dresses worn by our experiences, be able to acknowledge them as forms of becoming involved in both global and internal politics and offer them to academic language communities in ways which mediate plural conversation partners, so that they continue to aim for precision while being adapted for crossing borders.

All expression is a form of translation from the unspeakable experience to the conventions of a language. A particular expression may feel familiar and comfortable because one is accustomed to that form of expression or has practiced the use of that language and made it her own and also because others have used that language to express similar experiences forming a tradition of expression. But as an academic, irrespective of the language, discourse about contemplative literature implies a second level of translation – from the subjective expression to a careful unpacking of the nuances in a universal language. In being a scholar-practitioner, expressing contemplative experiences in a non-English language and introducing it to an English-speaking academic community means to unpack the nuances of the foreign language. Some words and phrases translate easily, some have approximate translations, some have cultural contexts which don’t carry over in translation and some have no corresponding translation of experience. One has to identify these zones of hermeneutic opacity and annotate them in “thick descriptions.” Such a process is a handshake between emic and etic descriptions. Can we locate something more universal beyond the boundaries of a culture? If not, one can leave it there. If we do, it takes a creative effort to translate across boundaries and communicate/transmit experience. We may ask, even if one does, will the essence be lost in translation? The question here is what one means by essence. There is an essence of a cultural expression which remains within the walls of the culture. For that matter, there is an essence to subcultural experiences of a cultural expression because cultures such as languages have dialects which carry meanings which are specific to subcultures. Further, each person experiences any expression in a unique way each time they encounter it. This is an aspect of the hard problem of consciousness. One may make it one’s research in contemplative studies to identify the elements of such untranslatable specificities and what they code for in experience. At the same time, all cultural expressions are dresses for impersonal experiences of consciousness which can be transmitted across borders in different dresses. One may make this one’s research in contemplative studies.