Debashish Banerji

Studies of the participation of art in the formation of nationalism have tended to emphasize its creation of national myths and a continuous history in the service of the nation-state. Whether of the secular materialist kind, Marxist or capitalist or the Orientalist spiritual kind, such historicism has also been viewed as derived inexorably from the discourse of post-Enlightenment modernity. While such determining paradigms have their utility and reality, they succeed in rendering invisible subtler realities of alternate nationalisms, which remain subjugated, because unable to be voiced within this discourse. On the broader historical canvas, the Subaltern Studies group has made its intention the recovery of such alternate nationalisms. However, while valuable for the understanding of subalternity as the voices of socially subjugated minorities, these studies too, have largely conceded to modernity the “mainstream” histories of nationalism. In his by now classic work The Nation and its Fragments, Partha Chatterjee, one of the founder-members of this group, has grappled with some of these complexities of nationalism, subalternity and modernity. Taking his examples of early mainstream nationalism from what has been called the “Bengal Renaissance” of 19th c. Calcutta, he has tried to contest a simple derivation of national identity formation among colonized people from western models and institutions. But in doing this, he has affirmed the Orientalist divide of the national bourgeois psycho-sphere into the distinct worlds of outer and inner, material and spiritual, historical and eternal, colonized and free.[1] However, his analysis is far from a simple reduction, its subtleties amplified and elaborated in the last few chapters, which deal with the ideologies of civil society and community[2]. Here, he reformulates his earlier and more obvious divide, showing at the same time how post-Enlightenment modernity (of which colonialism is an epiphenomenon) premises itself on the plural space of secular civil society and how such a space depends on taxonomic grids of determinable meaning to maintain its order. In opposition to this, he demonstrates a strand of the Bengal Renaissance, which defies the attempt at categorization, resisting determinacy and relationality and thus, causality and historicality. This strand, dialectically opposed to civil society, he sees as “the untheorized discourse of community.”[3] Dipesh Chakrabarty, another member of the Subaltern Studies group, in his more recent Provincializing Europe, begins in many ways, where Chatterjee’s text ends. Chakrabarty extends the definition of subalternity to cover events that resist historicization. In his words. “they are marginalized not because of any conscious intentions but because they represent moments or points at which the archive that the historian mines develops a degree of intractability with respect to the aims of professional history…. Subaltern pasts, in my sense of the term, do not belong exclusively to socially subordinate or subaltern groups, nor to minority identities alone…”[4] What Chatterjee calls “the untheorized discourse of community” would be considered subaltern in this sense and would be rejected by history writers, whether classical or contemporary, precisely because it would resist linkage in the causal narratives of the nation. Chakrabarty gives closer attention to this communitarian strand of the Bengal Renaissance in his book and attempts to sketch out a new location for it that would render it visible within history. Reiterating the premise of a plural secular civil society as the basis of the modern democratic nation, he points to the necessary formation of public and private domains for its existence. The revolutionary content of the Bengal Renaissance, he contends, was the creation of an alternate space that could exist alongside ordered civil society, a space that was neither public nor private, but stood liminally in-between, capable of offering subjective escape or of performatively subverting or negotiating transformation of the everyday order of civil society. This was the discourse of community, translated into the urban society of 19th c. Calcutta by a multiplication of means, prominent among which must be considered the creative efforts of the Bengal Renaissance. Chakrabarty isolates a number of devices by which this discourse is set in place, including the translation of a village sociality, relationally through extended familiality, actionally through practices such as adda, and ontologically through the formation of a heterogenous subject.[5] Of course, to locate the communitarian within the cultural politics of the Bengal Renaissance may be to risk the ire of Marxists and “traditional” Subaltern theorists alike. Limited within the boundaries of Hindu male bhadralok (gentlemen/bourgeois) society, this discourse of fraternity will be seen as an appropriation by the dominant/elite classes of the culture of the proletariat/subaltern. However, to do this is to fall prey to a structuralism which is blinded by its rhetoric into believing that taxonomies and polarities are truths and not strategies. While the interpretive division of society into bourgeois/proletariat or elite/subaltern is strategically important from the viewpoint of understanding and struggling against certain forms of subjugation, it is also and at least equally important to recognize that the condition of subjection to the forces of capital, whether economic or cultural, is a universal habitus of modernity and calls for a critique more fundamental than that of class struggle, as brought home in Moishe Postone’s recent reinterpretation of Marx.[6] According to Postone, the alienated social relationship of capitalism is ubiquitous and internal to modernity, capital and labor being co-constituents of personhood within it. In Postone’s words, “The modern capitalist world, according to Marx, is constituted by labor, and this process of social constitution is such that people are controlled by what they make. Marx analyzes capital as the alienated form of historically constituted, species-general knowledge and skills and, hence, grasps its increasingly destructive movement toward boundlessness as a movement of objectified human capacities that have become independent of human control.[7] From this point of view, the struggle against subjection can be seen as developing its own fuzzy forms within classes and sub-classes and spilling over to influence other social domains. The interpretive framing of struggle in terms of civil society and community, is thus strategic in a way in which certain aspects of the Bengal Renaissance can be seen as productive of a communitarianism which nevertheless developed its own life independent of class origin and continues as a messy component of contemporary life in Calcutta.

Extending Chakrabarty’s analysis, here I would like to suggest that this communitarian discourse was conceptualized by some of its inscribers as not only an alternate sociality, but as a model for an alternate national intersubjective space, one that could resist the leveling sway of the nation-state. And to his archive of devices, I would like to add the mytheme(s) of the Krishna Lila, the cycle of Krishna’s sports and dalliances with the cowherds and cowgirls of Brindavan, with its regional and national historical transformations, which comes to assume specific meanings in the urban national context of modern Calcutta.

Cultural nationalism, one may even say, is endemically plagued by the kind of ambiguity that the Bengal Renaissance demonstrates. Seeking for liberation from colonial subjection, it organizes collective identity in the form of taste, myth and history. The inevitable fossilization of such forms into authorized markers of the nation-state conflicts fundamentally with the drive for liberation, thus seeding the phenomenon with an internal dialectic. While in most cases this dialectic remains subliminal and unrecognized, it could surface as a source for ongoing productive revision within nationalism. My understanding of alternate nationalism stems from such a dialectic. The Bengal Renaissance, as an early pre-Swadeshi cultural movement, provides us with an interesting example of a nascent cultural politics, its dynamics moving fluidly between lived and imagined communities, locality, region and nation. The dialectic between form and freedom, structure and anti-structure, state and community is active within its discourse and the Krishna Lila mythos is an important medium for such transactions. This dialectic between the Apollonian and Dionysian potentia of nationalism[8] surfaces in the Bengal Renaissance through reasons both specific and general. Modernity and its ontology can be seen as the broader and more general determinant of an alienation against which culture may be seen to struggle through an adaptation of local communitarian and pastoral forms. But from the specific historical context of the region, this dialectic may be seen as a displacement of the analogous relationship between samsara and sannyasa, irrevocably ruptured by modernity. I have tried to develop this theme elsewhere[9] and will not elaborate here except to point out that it is this historical happenstance combined with the prevalence of alternate forms of structuring the same dynamic in Bengal that allows such a clear manifestation to the conflict within cultural nationalism and turns it into the basis of an alternate urban, social and national form.

The term “alternate nationalism” has sometimes been castigated as merely an attempt to reformulate a mainstream nationalism by positing something “more authentic.” To this view, the drive for nationalism is fundamentally tainted by its need for rational validity, the causal chain of a history that can stand only through its suppression of all untidy incidentals which disturb its narrative. The national field is therefore of necessity a contested one, where histories jostle for supremacy in the words of a variety of myth-makers. To a mainstream history there are always a number of alternate versions, spectral histories which roam the streets in search of a home and occasionally find receptive grounds for rebellion and overthrow in the name of authenticity. There is thus no good or bad nationalism, only nationalisms that vie for supremacy. The voice of the intellectual must be raised against this very phenomenon called nationalism, according to this view, and support for any version of nationalism, alternate or otherwise, should be treated as suspect. But as Chatterjee points out, irrespective of the utopianism of this stance, the institutional hold of nationalism as a determining regime of contemporaneity is so settled and pervasive that it cannot merely be wished away by denying its existence.[10] If we recognize the internal dialectic of cultural nationalism, the notion of an alternate nationalism takes on a different and more radical sense. According to this, nationalism is contested not merely by other versions of itself but by its opposite, an anti-nationalism, which constitutes it as much as is constituted by it. It is in this sense that the challenge to colonialism, urbanity and modernity represented by myths such as that of the Krishna Lila, while itself the harbinger of a new regionality and nationality, can be seen as equally the destroyer of these forms, a dissolution through an appeal to community in the face of state identity. The continued co-existence of such forms of nationalism and its alternates, may lead to a culture of ceaseless revision, where the form of the nation is rendered pliable and creatively dynamic, while ceding ground progressively to the utopic dream of community and philosophic anarchy.

The Krishna Lila paintings, a series of 23 watercolor miniatures on the sports of the cowherd incarnation of Vishnu, are considered to be the point of departure for the artist Abanindranath Tagore, founder of the Bengal School of art. Prior to this, Abanindranath had some European academic training in art from an Italian artist, Olinto Gilhardi and an English teacher of oil and water colors, Charles Palmer. Abanindranath did not complete his studies under Palmer, but the Krishna Lila paintings betray his English watercolor training in his treatment of background landscape. Palmer seems to have been sympathetic towards his aversion to academic training and commented to Jamini Gangooly, Abanindranath’s nephew and co-student, “I had noticed all along that your uncle could not pull on with ‘life study’ and the European principles of light and shade…. It is a good sign that the artist’s temperament revolts against all rigid rules and beaten tracks. Independence leads to personality in art.”[11] When he saw the Krishna Lila paintings, he encouraged Abanindranath: “Mr. Tagore, I should strongly advise you to proceed along this line and produce more pictures of a similar nature. These pictures have a character of their own. You require no studies from life any more. I shall be greatly pleased to see your work from time to time.”[12] The paintings were made in 1897/8, at a time when the literary expression of the Bengal Renaissance was already well established. Born into the bhadralok family of the Jorasanko Tagores, Abanindranath found himself in the thick of the Bengal Renaissance from his childhood. In the shadow of the entrepreneur Dwarkanath Tagore (1794-1846), the milieu of the Jorasanko Tagores into which Abanindranath was born was prominent in the fashioning of various strands of the Bengal Renaissance. Interpretive debates and creative revisions and expressions in the field of religion and literature and cultural events like the Hindu Mela were ongoing concerns in this house and Abanindranath was no doubt socialized into the habitus of cultural nationalism from an early age. Two significant forms of regional mystic and cultic practice which found prominent articulation in the Bengal Renaissance, were Shaktism and Vaishnavism. Of these, it is the urban adaptation of the second at the turn of the 19th/20th c. in Calcutta which interests me here. As paintings, Abanindranath’s Krishna Lila universalizes the literary messages of Vaishnavism in the Bengal Renaissance, but goes further in its creative handling of textuality. While images undoubtedly transcend their textuality, the multivocality of images renders them meaningful in different and untranslatable ways to a diversity of viewership. The articulation and creative exploitation of such textual diversity within the image opens up an intersubjective dialogic space, where continuities and discontinuities are acknowledged and put into negotiation. My contention here is that Abanindranath’s Krishna Lila initiates such a process, which I try to explore in my discussions below on heterodoxy and on the plurality of life-worlds of the modern subject citizen of late 19th c. Calcutta/India, in which the paintings are embedded and which they address variously.

The polysemic possibilities coded into Vaishnavism, from the beginnings of its 8th/9th c. textual appearance in the Bhagavat Purana, have lent themselves to diverse adaptations through the regional history of Bengal and extending therefrom, in national and local histories, such as that of Jorasanko, the extended household of the Tagores. The compounding of the aesthetic, the erotic and the devotional in Sanskrit literature goes back to canonical writings such as the 2nd c. Natyashastra of Bharata and its extensive application in the 5th c. courtly literature of the Guptas-Vakatakas.[13] The 10th chapter of the Bhagavata Purana[14], dealing with the emotional life of the growing cowherd avatar Krishna, particularly his relations with the cowgirls of Vraja, is presented along these lines. The alliance of aesthetic, erotic and devotional constituents in this cycle of spiritual romance has lent itself to a variety of mutable emphases in different locales, periods and milieus depending on contextual circumstances. An outline of such a genealogy would bring to light the specific accretions of meaning present at the threshold of modernity in 19th c. Calcutta and their semantic transformations in this context, generally in the Bengal Renaissance and specially, to the creative handling of the Krishna Lila paintings.

Though a thorough historical treatment goes beyond the scope of this chapter, some broad lines in the adaptation of the Krishna Lila in Bengal may be indicated. The earliest known literary retelling of the Krishna Lila mythos in Bengal is Jayadeb’s 12th c. Geeta Govinda. Jayadeb’s poem is written in a highly aestheticized courtly Sanskrit and amplifies the erotic sentiment present in the Bhagavat Purana by transferring the collective ardors of the Brindavan cowgirls to the individualized subjective interiority of Radha, the feminine counterpart to Krishna. At the same time, his characterization of Krishna as both master and slave of love opens up the way for doctrinal innovations fully exploited by 16th c. Vaishnav theologians. The circulation of the Geeta Govinda throughout the Indian subcontinent over the next centuries made it into one of the most popular pan-Indian texts on the Krishna Lila and an important source (along with the Bhagavata Purana) for Rajput and Pahari painting from the 17th c. on. In Bengal, over the next four centuries, its themes and sentiments were vernacularized into Brajabuli and old Bangla by poets such as Baru Chandidas, Chandidas and Vidyapati, increasing the popular appeal of the mythos and introducing its ideas into the mix of erotico-mystical heterodox cults of the region such as the Sahajiyas, Tantrics and Buddhists.[15] Following this period, Sri Chaitanya (1486-1533) is responsible for the most powerful popular formulation of the Krishna Lila cult and the birth of a formal Bengal (Gaudiya) Vaishnavism. Chaitanya’s approach drew on both Sanskrit and vernacular poems on the Krishna Lila theme and made these into occasions of ecstatic collective contemplation facilitated by singing and dancing. Chaitanya also broke orthodox Hindu sectarian and casteist lines and opened the practice of his mystical Vaishnavism unconditionally to all.[16]

In this respect, it may be valuable to note that while positioning itself at the periphery of Hindu religious practice, the Krishna Lila cultus in Bengal also found itself from the beginning intimately related to Islam. Jayadeb himself was connected to the court of Lakshman Sen (c. 1178-1206), whose reign ends with the establishment of Turko-Islamic rule in the region. The proliferation of Islam as a hegemonic religious doctrine lacking shared roots with the history of regional spiritual discourse created a situation which may be better understood using Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of doxa.[17] According to Bourdieu, doxa are the unquestioned assumptions of a society, fossilized through historical processes so that there is a perfect congruence between the objective order and structures of consciousness.[18] These cultural practices and dispositions are therefore taken to be fixed and without alternatives. The forcible introduction of culture(s) with entirely independent historical roots into this matrix reveal the arbitrariness of doxa on both sides, releasing them potentially as choices. What were previously choiceless doxa now bifurcate into orthodoxy and heterodoxy.[19] The role of mythemes in facilitating processes of heterodox innovations under conditions of alien culture contact is attested to by the Krishna Lila. The suggestive, transgressive and polysemic possibilities of the Krishna Lila mythos formed a powerful catalyzing force in this period from the 12th – 16 th c. in fostering a plethora of heterodox mystic cults in Bengal and in providing them with variant approaches to a common thematic. Thus Baul, Sahajiya, Natha and a variety of sects and cults found themselves sharing a creatively handled vocabulary with Islamic mystic sects such as Fakirs, Pirs and Sufis.[20] This situation continues till today in rural Bengal, loosely institutionalized around collective festivals such as the Baul and Fakir Melas.[21] In the 16th c., the coming of Chaitanya added to this element of heterodoxy a powerful uniting force through an utopic social eschatology of communitas.[22] I use the term ‘communitas’ in the sense given by anthropologist Victor Turner, where he sees the hierarchic rigidities of social structure spawning the yearning for the experience of their opposite – an unstructured euphoric fraternal unity. Turner, in his work The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure deals with a variety of historical and cultural instances of communitas, of which one is the movement founded by Chaitanya.[23] Though in this exposition, Turner mistakes Chaitanya’s brand of Vaishnavism with the Sahajiya cult, the important identification he makes here is that of seeing Chaitanya’s adaptation of the Krishna Lila as not a temporary euphoric release as in most cases of communitas, but a form of partial withdrawal from the structures of society so as to institutionalize an alternate social form of “permanent communitas.”[24]

This history of medieval heterodoxy and the part played in it by the Krishna Lila is interestingly analogous to the urban situation of 18th/19th c. Calcutta. Here, the Islamic presence can be seen as replaced by colonial modernity, with the pressure of its new civilizing teleology and totalistic epistemology leading towards the formation of modern civil society with its division into public and private domains. For some Bengalis of the 18th c., this alien cultural hegemony served to open up an unsettled space of “jurisdictional uncertainty”[25], where doxa could once more be re-negotiated and orthodox and heterodox formations separate.[26] Here, it is often individuals and families already aligned with the history of heterodoxy in the medieval period which exercised their social creativity in this new urban space and a continued adaptation of the post-Chaitanya Krishna Lila mythos to stake out a domain of social communitas against the new orthodoxies of civil society which gains diverse interpretation.

Thus, in talking about Abanindranath Tagore’s Krishna Lila paintings, it is important to locate their social roots in the Jessore Vaishnav Brahmin family of Kusharis, outcast from Hindu society in the 15th c, due to an apocryphal incident in a Muslim court, and known popularly thenceforth as ‘Pirali’ (or quasi-Muslim) Brahmins. The ‘Tagores’ are a branch of this outcaste family settled in the vicinity of the new colonial city of Calcutta in the late 17th c. and the “Jorasanko” Tagores a further sub-branch, claiming possession of the family deity or aniconic stone (shalagram) form of Vishnu/Krishna. As touched on earlier, the prominence of this branch of the Tagores in the early colonial period can be traced to the mercantile liaisons and negotiations of Dwarkanath Tagore, the grandfather of the poet Rabindranath and great-grandfather of Abanindranath.[27] In this formative phase of the city, Dwarkanath’s uncertain social identity was an advantage which he exploited to the full in his dealings with the cultural plurality of the urban space.[28]

Dwarkanath’s eldest son and Rabindranath’s father, Debendranath embraced the synthetic universalism of Rammohun Roy’s Brahmo faith. Undoubtedly, among other things, it satisfied a longing for religious legitimacy, achieved through creative transcendence, while eschewing orthodoxy. Rabindranath followed in his father’s footsteps and remained an active member of the branch of Brahmoism led by Debendranath. Though this section of the Jorasanko Tagores abandoned Hindu ritual and idol worship and discarded the stone family icon, in the writings of both Debendranath and Rabindranath, one sees a continuation of the Krishna Lila references, metaphors and philosophemes. In the case of Rabindranath, in fact, there is a deliberate self-fashioning through physical appearance, dress and literary expression of an identity based on the tradition of the heterodox medieval Vaishnav cults of Bengal, particularly the Baul/Fakir forms.[29]

Debendranath’s brother and Abanindranath’s grandfather, Girindranath retained the stone shalagram idol and the Hindu self-identification, so that he and his descendents can be seen as more orthodox Gaudiya Vaishnavs among the Jorasanko Tagores.[30] Nevertheless, all branches of the Tagores continued to share a ‘Pirali’ questionable status in the eyes of mainstream Hindu society of the time, so that however they positioned themselves, this liminality combined with the post-Chaitanya legacy of Vaishnavism, freed them to pursue lifestyles and expressions of creative interpretation with close interchange across sectarian borders.

In 1877, Rabindranath published his first poems in the new Jorasanko house journal Bharati. These were a set of Krishna Lila poems written in old Bengali (Braja-bhasha) under the pseudonym Bhanusingha and posing as unknown authentic medieval Vaishnav poems discovered in the Brahmo Samaj library.[31] A decade later, observing his nephew Abanindranath’s restlessness with English watercolors, he advised him to turn to the medieval Vaishnav padabali literature and mine the treasures of the Krishna Lila in his art. In 1897, Abanindranath marked his departure from the themes and techniques of his tutelage with the Krishna Lila paintings. Reminiscing later on these paintings, Abanindranath identifies two simultaneous influences inspiring their genesis – the post-pre-Raphaelite illustrations to a book of Irish ballads gifted to him at that time and an album of 19th c. Indian paintings of the Delhi School.[32] In this performative disclosure he sets up the heterodox hybrid origin of the series. He also points out that Balendranath Tagore wrote an article on the same Delhi School paintings for Bharati. Balendranath’s article in Bharati was titled ‘Dillir Chitrashalika’ (the Delhi School of Art).[33] The subtext of the article is the contrast between the world of the Delhi School paintings and modern Calcutta. To summarize, the paintings present a world of intimate relationships – each individual is distinctly drawn yet each contributes some episodic detail which adds up to establish a context of unified meanings and relationships, a community. It is this communitarian message in its opposition to the fragmenting power of modernity that Abanindranath was drawing attention to in Balendranath’s essay and by extension to the art of both the Delhi School and that of the Pre-Raphaelites. In 1896/7, Abanindranath also met for the first time, E.B. Havell, his mentor-to-be from the Govt. Art College, from whom he picked up the anti-materialist critique of the British Arts and Crafts movement. It is unclear whether Abanindrnath met Havell before or after painting the Krishna Lila, but in either case, he seems to have intuited some of the latter’s ideas of the critique of modernity and the espousal of integrated cultural environments.[34] Thus, when Abanindranath speaks of the homologies between the Irish ballad illustrations and the Patna School paintings, it is their common affiliation to oral traditions of poetry and song and their spiritual and communitarian contexts that play an important part in his identification. Moreover, he positions them as British and post-Mughal -and thus, international and national – peripheries of the Krishna Lila paintings.

Abanindranath’s Krishna Lila paintings are executed as miniatures on paper, typically of size 5” x 8”. Of the 23 paintings in the series, 7 have inscriptions which take up almost half the page. Of these, five are in Sanskrit and two in medieval Bengali. The paintings display a consistent style – the figures are stiff and typal, closer to the manner of the early medieval Chaurapachasika style which continues in some of the later miniature schools, such as Basholi. In this, there seems to be an attempt to develop a figure type belonging to the Gujarat-Rajasthan-west Uttar Pradesh region, thereby acknowledging a location for the events in a more concrete national space, as against a purely idealized mystical space. But the landscape and architectural settings are hardly in the flat simplified highly contrasting opaque colors of the Chaurapanchasika style, substituting a preference instead for a naturalistic muted English watercolor treatment. I will deal further with the implications of style when discussing the emotional content of the paintings.

Here, I would like to isolate some of the key features of the Krishna Lila paintings signaling transformations of post-Chaitanya Bengal Vaishnavism in their specific relevance to modernity and the fashioning of an alternate regional, national and trans-national urbanity:

1.) Heterodoxy and Social Immanence: I have indicated how the regional history of Vaishnavism in Bengal had developed a strong tradition of heterodoxy by the modern period.[35] This included the burgeoning of a large number of syncretic cults incorporating diverse mixtures and variations of Buddhist, Tantric, Vedantic and Islamic/Sufi positions and practices, rendering the field doctrinally malleable and mystically fertile. Of course, there also developed side by side, a fundamentalist Gaudiya orthodoxy, but even this was marked by its relative collapse of caste and class distinctions.[36] The popularity of Krishna Lila themes overflowed sectarian boundaries. Krishna Lila themes and metaphors are reiterated even in Muslim circles through mystical folk songs such as fakir gaan[37] and a perusal of post-Chaitanya collections of Krishna Lila poems or padabalis reveals a substantial number of Muslim poets (pada-kartas).[38]

The new pluralistic urban sphere of Calcutta was peculiarly suited to the development of a creative non-sectarian rhetoric of immanent mysticism based on Vaishnavism. The Jorasanko Tagores, as mentioned above, were important players in the formation of the cultural identity of gentleman/bhadralok society here and in spite of their split into Brahmo and Gaudiya branches, shared a hybrid ‘Pirali’ self-identification creatively straddling heterodox traditions. In both the Brahmo Rabindranath and the nominally Gaudiya Abanindranath, Vedantic, Vaishnav and Sufi elements mixed freely in a self-styled aesthetic mysticism of social and natural immanence. In the case of the Krishna Lila paintings, their heterogeneity is affirmed at the outset through a deliberate disclosure of the art-object’s textuality as a form of mutual equivalence – art is text as text is art. Historically, this choice offers a challenge to the post-Renaissance culture of specialized visual connoisseurship, itself an instance of modernity’s systemic classification and ordering of the world.[39] Here, though the artistic weaving of text and art undoubtedly follows earlier traditions of Persian/Mughal illustrations, the self-consciousness of Abanindranath’s

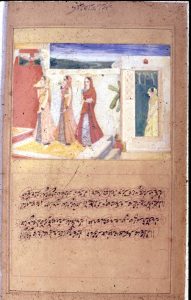

Figure 1 – Bhabollasa/Abanindranath Tagore (RBS)

visual handling of textuality is without precedent. A Persian calligraphic script (nakshi) is invented to make legible the Bengali alphabet which in turn voices Sanskrit poetry.[40]

One can observe this, for instance in the painting “Bhabollasa” [Figure 1]. The theme deals with the preparation for the moment of union. Cloistered in an interior indicative of her subjective isolation, Radha’s expectation readies the celebration of ecstatic encounter. The inscription reads (in translation):

Prepare the bed with flowers; bring, too, immortal garlands like strings of pearl. Bring clothes fit for dalliance with my beloved friend. Bring betel leaf in a jeweled case. Bring the yellow dress for the night. Know you all that the time for unhindered eternal union with Madhava comes shortly.

This jubilant mood accompanying mystical consummation has been celebrated by innumerable Hindu and Sufi poets alike in South Asia and forms a common theme of songs sung to this day from the time of Amir Khusrau (13th c). At the same time, it opens cultural doors on secular celebrations such as South Asian marriage festivities with their opulent forms of communal sharing. The painting, dealing with the preparations is austere and iconic, but manages through this understatement to suggest more than it says. The lady friends of Radha carrying the paraphernalia of celebration, remind us that union, mystical or secular, occurs in a collective context. The hanging garlands, banana leaves and earthen pot topped by an unripe coconut indicate Hindu ritual festivals, such as of marriage. They also point to what Abanindranath in his later writings, terms as a non-Aryan or anyavrata layer of culture hybridized into Hindu rituals.[41] However, the sparseness of detail also leaves room for interpretation and negotiation by a variety of regional and national constituents who may identify with the theme, while in the inscription, four levels of historicity are visually brought together through translational linkages which set into motion a regional and national dialogic space: from a distance, the inscription has the look of Persian calligraphy and pleases by its abstract aesthetic. Closer scrutiny reveals the alphabet as Bengali, while actual reading of the text shows it to be Sanskrit. The paintings thus participate in the oral traditions of Sanskrit poets who have been vernacularized and Islamicized, with the necessary independence through refraction at each translational level. It faces the viewer in the present as the modern art-object, ready for international consumption, constituted through the universal aesthesis of abstract calligraphic surface, yet like the urban space of the artist’s

Figure 2 – Abhisarika/Abanindranath Tagore (Indian Museum, Kolkata)

city, marked with the unsettled living and open secrets of its present pasts.

2.) Affective Rationality and Emotional Excess: The intersection of aesthetic, erotic and devotional attributes in early Bengal Vaishnavism received a new popular formulation in the 16th c by Chaitanya, which prioritized the emotional over the physical body.[42] This isolation of the “body of feelings” played an important role in identifying the location of truth and authenticity within the emotional body during the Bengal Renaissance. The novels of Sarat Chandra Chatterjee (1876-1938), for example, locate female “purity” in an interior ‘authenticity’ of feelings rather than in the forced circumstances of subjugated bodies under colonialism.[43] In saying this, I am aware that it implies the traditionally theorized split between the outer material domain where physical bodies were compromised and subject to the forces of coloniality and modernity and an inner domain of freedom and self-determination. However, I do not see these domains as watertight entities, nor do I identify the inner domain with the spiritual as opposed to the material. The emotional body here mediates between material and spiritual realms, providing a vantage for negotiating and structuring reality based on what Esha De has

Figure 3 – Krishna Lila: Nau Bihar/Abanindranath Tagore (RBS)

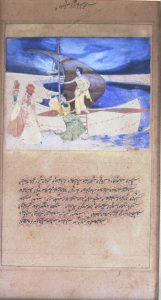

termed a “feeling-ordered” or “affective rationality.”[44] De, following Foucault, sees the domain of reason as non-uniform, thus identifying plural rationalities. As against the “instrumental reason” of post-Enlightenment modernity, she locates an “affective rationality” which follows a creative logic driven by a specified succession of emotional states. In the Indian context, she sees the various formulations, elite and popular/subaltern, of rasa sastra as instances of such a “feeling-ordered” or “affective” rationality, mediating between material and spiritual realms.[45] As indicated earlier, the epistemes for such mediation go back at least to Bharata’s theories of rasa aesthetics, and their repeated applications and interpretations. The complex elaboration of these ideas as an emotional/aesthetic mysticism in the 10th c. by Abhinavagupta[46] gave them a new discursive power, generating a large body of textual and practical forms in the succeeding centuries. Post-Chaitanya Vaishnava theologians, particularly the writers of Gaudiya doctrine known as the Brindavan Goswamins[47], were prominent for the adaptation of rasa throry to the Krishna Lila. According to this, contemplation of the pastimes of Krishna would awaken specific experiences of mystical emotion in an ordered hierarchy of ecstatic release/union.

The figure of the Abhisarika is a good example of a mediation between material and spiritual domains in Vaishnava rasa-aesthetics. The Abhisarika is a married woman with a stable location in the material order of the social world. But attracted irresistibly to Krishna, she steals away from home for her illicit tryst. Her path traces the movement of emotion in the experience of rasa – not one of simple transcendence but a transgressive movement between two forms of embodiment – material and spiritual. It is the fertile ambiguity of this image that makes it such a creative trope in the vocabulary of rasa-aesthetics.[48] The Abhisarika appears at least thrice in Abanindranath’s paintings – once within the Krishna Lila series and once each before and after, bracketing the series. The Abhisarika image is not bound within the sectarian concerns of Vaishnav schools, having been imported into its canon from earlier formulations of rasa imagery, such as Kalidasa’s 5th c. Ritu Samhara (Cycle of Seasons). Abanindranath was aware of this, as his post-Krishna Lila Abhisarika [Figure 2] was presented in this context, with Kalidasa’s inscription for calligraphy. Thus a non-sectarian aesthetic mysticism is isolated by Abanindranath of which the emotional states of the Krishna Lila are presented as socially embedded instances. Here, an ‘affective rationality’ works through a classification of human relations and their presentation as archetypal situations porous to a mutable and often transgressive action of affect. Such action achieves its radical power through a participatory culture of emotional excess where the rhetoric of unconditional surrender counters the objectification and commodification of relations as measured exchange introduced by modernity and its institutional forms organized through the nation-state and national and multi-national capital. A situation in the Krishna Lila paintings exemplifying such an affective transgression within what may be seen as a commercial exchange, is to be found in the painting titled “Nau Bihar” (Boat Dalliance) [Figure 3]. Here again, the painting is divided vertically into equal parts of image and text. The image shows a boat with sail unfurled docked on a bank edging the dark blue waters of the Jamuna and dividing it from a moody atmospheric sky of the same color. A light-ash-blue Krishna stands on the boat in dhoti and chaddar, gesticulating with an extended right hand while he holds the left hand of a green sari clad Radha with his own left hand. Radha has one leg on the shore and another lifted as if to enter the boat. Her head is turned back towards two other standing women in saris with pitchers on their heads. Apart from the blue of the water and the sky and some green colored stripes on the oar extending from the boat, Radha, at the center of the image is depicted in a bright elaborately designed green sari and green blouse, capturing the attention. The text inscription below, this time voicing an old Bengali pada (lyric) by the poet Gyandas, is written in the Bengali alphabet, scripted once more in Persian/Urdu nakshi calligraphy. It reads in translation:

Tell, o friends, what should I do

Being a boatman this one is asking for my youth.

A cause for alarm, o friend, fraught with danger

The boatman has put around my neck his own garland.

What was in my fate, o friend, who can change that

Being a boatman (he) touches me as he speaks.

It is shameful, o friend, a canker on my repute

With force and cunning the boatman has taken me on his lap.

Gyandas says, O girl, do not despair

Nanda’s Delight is the boatman, what need is there to fear. [49]

Here, Radha and her cowgirl friends, their pots filled with water, are making to cross the river in a boat at sunset. What is an everyday commercial transaction suddenly crosses the borders of propriety and enters a liminal zone of communitarian affect where the emotional life subverts the material exchange through the opening of an erotico-mystical experience of transcendence. In the painting, Radha is shown half-turned, as if in-between the two worlds of material exchange and mystical union, translatable in the context of Abanindranath’s Calcutta as the corresponding worlds of modernity with its ontology of the commodification of lives and relations and communitas with its immanent spirituality. The transgressive movement of the “body of feelings” passes from materiality through eros to spirituality – a movement between two embodied states as imaged by Radha’s pitcher-carrying friends and Krishna respectively. The friends still belong to the world of material transactions, while Krishna in his boat who guides the “shameful” transgressive movement of eros or affect has been specified in the calligraphic lines by Gyandas as “Nanda’s Delight,” from whom “there is no need to fear” – that is, the embodied object of transcendental identity, while Radha as the visual focus of our attention is the liminal transitive engagement between these two worlds. A subtler but similar in-between-ness can be seen in the posture of Abanindrnaath’s post-Krishna-Lila Abhisarika [Figure 2]. Though this nayika figure is alone in the dark with no context pictured behind or before her, there is a furtive twist to the slender body which marks the movement of affect as an engagement between two embodied experiences – that of materiality and spirituality or the world of contractual and commodified relations (modernity) and the world of the ecstatic identity of communitas (community).

In Abanindranath’s paintings, the isolation of the emotional body is also reflected in a deliberate departure from the fleshliness of the traditional Bengali depictions of the Krishna Lila.[50] Moreover, unlike the fluid easy charm of Pahari paintings, which figure both space and time as leisurely movement and seduce the eye to a natural identification and enjoyment, Abanindranath’s paintings with their rigid forms and staccato movements are like scenes forced into slow motion and frozen into frames, which distance the eye by their iconicity. With their abbreviated inscribed titles (about which, more later), they function more as mnemonics in an emotional alphabet, which is being presented so as to reinforce an alternate worlding of the world.[51] The transcendental world of mystical experiences thus becomes immanent in social relations as archetypes of feeling, which through intensity of contemplation, may open the door to liberation through the experience of rasa.[52] The gamut of emotional relations, from the carnivalesque participation of the entire town in the birth of Krishna, through filial, fraternal and specially various aestheticized stages of romantic affect, are elaborated in the paintings, with an intensity of mood sometimes bordering on hysteria. An image which captures well this extreme affect is Akrur Samvad [Figure 4]. The incident has to do with the arrival in Brindavan of Akrur, a friend and relative of Krishna’s, come to take him and Balaram to Mathura for the episode leading to Kamsa’s slaying. The cowgirls of Brindavan, knowing that Krishna will desert them, are distraught.

Figure 4 – Akrur Samvad/Abanindranath Tagore (RBS)

Abanindranath’s painting shows us an inner courtyard with an open door to the outside through which a glimpse of a ready chariot with Krishna in it can be seen. Centrally foregrounded in the courtyard are four women in saris, with two of them holding up a third who has swooned and in the process of falling to the ground. The text inscription occupying the bottom half of the painting, is once more in Sanskrit written using Bengali characters in a Persian calligraphic style, The lines here are taken from the canonical Vishnav text, the Srimad Bhagavata and echo the emotional excess of the cowgirls (gopis) upon hearing of Krishna’s departure: “O creator, there is no compassion anywhere in thee. Thou dost make creatures meet in friendship and love, and separatest them for nothing, before they are fulfilled. Thy work is like the sport of a child. Having presented to us Mukunda’s face, graceful under curly locks, with well-formed cheeks and prominent nose, most winsome with gentle smiles that overcome all grief, that thou takest him from our view is no good work on thy part.”[53]

This isolation of the “body of emotions” and heightened presentation of extreme affect in a dramatic scene works at subverting the instrumental order of objectified mundane life which characterizes the ontology of modernity, opening an unpredictable door to mystical experience. The swooning of the gopi through excess of emotion is also seen in mystical Vishnavism as an entry into a different order of “divine” reality through trance. Indeed, the “swooning” of the gopi in the painting in a heterodox context echoes the Sufi experience of fanaa (nonduality) often presaged by a trance of fainting. Thus, Abanindranath attempts to adapt the Krishna Lila mythos through the trope of emotional excess in an order of affective rationality, to reposition mysticism and its alternate experiences in the field of modernity.

3.) Collective Ecstasy: The Krishna Lila mythos presents its climax as the utopian moment of a collective union and ecstasy, not through the disappearance of the individual (as in Advaita) but through an ontological shift resulting in the realization of an euphoric participatory oneness. This climactic episode is known as the Ras.[54] Here the cowgirls of Vraja all dance in a circle around Krishna, but find at one point that Krishna has multiplied himself so as to be dancing individually with each of them. Each then experiences the unity of the all, while also preserving an intimate individual relationship with Krishna. In Abanindranath’s depiction of the Ras [Figure 5], his self-imposed naturalistic constraint prevents him from depicting the

Figure 5 – Ras/Abanindranath Tagore (RBS)

miraculous multiplication. Krishna and the gopis dance around a tree with Radha taking pride of place beside Krishna, as in Jayadeva. Without going into the doctrinal specifics of this realization, I would like to draw attention to a form of participatory action introduced by Sri Chaitanya in the 16th c. translating this paradigm into the popular culture of Bengal. This is the kirtan, a form of collective singing and dancing resulting in states of altered consciousness and loss of social distinction. The popularity of kirtan at all levels of society in 19th c. Calcutta can hardly be overemphasized.[55] Though Turner, in his discussion of Chaitanya fails to mention kirtan, as an anti-structural practice which positions itself at the periphery or limit condition of modern sociality, it is obviously a primary device for “communitas.”[56] Kirtans were common at the Jorasanko Tagore house. In the context of Abanindranath’s Krishna Lila paintings, these indeed play a central role. The Krishna Lila paintings have for some reason been universally misidentified as illustrations of Jayadeb’s Geeta-Govinda.[57] In fact, only one of the paintings can be clearly related to this text, the verse-inscriptions being from a variety of Sanskrit and Bengali padabalis. Rather, what unifies this body of work, is the fact that the Bengali captions to the paintings each refer to an episode or pala traditionally elaborated in pala-kirtans.[58] Indeed, the coding of such a nomenclature can be traced to the doctrinal aestheticization of the Krishna Lila by the Brindavan Goswamins.[59] As explained above, each pala coded a mnemonic in a structure of rasas. During the consolidation of Vaishnavism in Bengal following Chaitanya, numerous compilations of padabalis, organized by palas, were published.[60] This classification followed the expanding popularity of kirtan-singing and was meant to facilitate pala-kirtans. Though it is nam-samkirtan (repetition of the Name) which is participatory and collective in the full sense and pala-kirtans along with katha-katha usually conducted in a performative context, often through folk-plays or jatra, the aspect of collective ecstacy and communitas in pala-kirtan is undeniable.[61] The Krishna Lila paintings therefore, metonymically subtend a multi-sensory experience grounded in the collective ecstasy of the kirtan.

In this way, by locating the Krishna Lila paintings within epistemes of social transformation in turn-of-the-century Calcutta they can be shown to further the communitarian discourse of the Bengal Renaissance. More specifically, the paintings acknowledge the emerging vectors of regionalism and nationalism (as also a more abstract internationalism) through the presentation of a popular regional and pan-Indian myth while at the same time contesting the statist fossilization of these spaces through the deployment of visual means exposing and promoting a liminal intersubjective space within modernity characterized by negotiations of heterodoxy, feeling-ordered rationality and communitas.

[1] Chatterjee, Partha, The Nation and its Fragments: Colonial and Postcolonial Histories, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1993, pp. 12-13.

[2] Ibid., p. 200-40.

[3] Ibid., p. 238-9.

[4] Chakrabarty, Dipesh, Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference, Princeton and Oxford 2000, p. 101.

[5] Chakrabarty, Dipesh, Op. cit., pp. 117-214

[6] Postone, Moishe, Time, Labor and Social Domination: A Reinterpretation of Marx’s Critical Theory, Cambridge 1996.

[7] Ibid,, p.384.

[8] Here I would like to acknowledge my colleague John Tran, from the workshop on Modernity and National Identity in Art, for having pointed me to Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy as a text for deriving these conflictual categories of cultural nationalism. See Nietzsche, Friedrich, trans. Fadiman, Clifton P., The Birth of Tragedy, Dover New York 1995 reprint.

[9] Banerji, Debashish, “East-West Revisions of Hindu Spiritual Thought in Late 19th/Early 20th c. Bengal”, unpublished paper, 2000.

[10] Chatterjee, Op cit., p. 112

[11] Ganguly, J.P., “Early Reminiscences,” Viswa-Bharati Quarterly (Abanindra Number), Shantiniketan, 1942, p. 20.

[12] Ibid., p. 20-1.

[13] Though one may expect the dominance of the aesthetic and erotic to be peculiar to elite courtly culture, the provenance of the erotico-aesthetic as an independent genre of spirituality can be equally attributed to the seeking for forms of universality among professional itinerant artist communities and followers of cultic practice among a diversity of sects in an era of political integration.

[14] Srimad Bhagavatam, trans. Ragunathan, N., Vol II, Vighneswara Publishing House Madras, 1981 reprint, pp. 243-280.

[15] The rigid distinction between elite/written literatures and popular/oral ones is rarely an accurate model in the Indian context. Even the Marxist historian Sumit Sarkar, who makes the exploration of this distinction one of his objectives in his important paper on Ramakrishna is forced to concede the malleability of these domains. See Sarkar, Sumit, “’Kaliyuga’, ‘Chakri’ and ‘Bhakti’: Ramakrishna and his Times” in Economic and Political Weekly, Calcutta, July 18, 1992, pg. 1551.

[16] De, Sushil Kumar, Early History of the Vaishnava Faith and Movement in Bengal, Firma KLM Private Ltd., Calcutta, 2nd ed. 1961, 1986 reprint, pgs. 67-103.

[17] Bourdieu, Pierre, Outline of a Theory of Practice, Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, 1997 reprint, pp. 159-71.

[18] Krais, Beate, Gender and Symbolic Violence in Craig Calhoun, Edeward LiPuma and Moishe Postone ed., Bourdieu: Critical Perspectives, Chicago 1993, p. 167.

[19] Bourdieu, Ibid.

[20] Dasgupta, Sashibhusan, Obscure Religious Cults, Firma KLM Private Limited, Calcutta, 1st. ed 1946, reprint 1995, pgs. 160-7.

[21] Wulff, Donna M., “The Play of Emotion: Lilakirtan in Bengal” in William S. Sax ed., The Gods at Play: Lila in South Asia, Oxford University Press, New York, 1995, pg. 100.

[22] De, Sushil Kumar, Op. cit., pgs. 79-80.

[23] Turner, Victor, The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure, Aldine de Gruyter, Hawthorne, N.Y., 1969, 1995, pgs. 154-64.

[24] Norvin Hein sees the idea of lila (play as essence of reality) as a compensation for the lack of freedom in political, social and religious spheres during Muslim rule in India. See Hein, Norvin, “A Revolution in Krsnaism: The Cult of Gopala”, History of Religions 25, no. 4 [May 1986], pgs. 296-317.

[25] See Bhabha, Homi K., The Commitment to Theory, New Formations, Summer 1988, at 5, 22.

[26] Bourdieu, Op cit..

[27] Dutta, Krishna and Robinson, Andrew, Rabindranath Tagore: The Myriad-Minded Man, St. Martin’s Press, New York, 1996, pg. 17-26.

[28] Rabindranath, reminiscing in a lecture, had this to say about his childhood: “My ancestors came floating to Calcutta upon the earliest tide of the fluctuating fortune of the East India Company. The unconventional code of life for our family has been a confluence of three cultures, Hindu, Mohammedan and British. …I came to a world in which the modern city-bred spirit of progress had just triumphed over the lush green life of our ancient village community. Though the trampling process was almost complete….something of the past lingered over the wreckage..”. Ibid., pg. 17.

[29] This is what has led Sashibhusan Dasgupta, to call Rabindranath “the greatest of the Bauls of Bengal.” Dasgupta, Sashibhusan, Op. Cit., pg. 187. Ed Dimock follows Dasgupta’s lead elaborating this theme in a paper titled ‘The Greatest of the Bauls of Bengal”. Dimock, Edward C., Jr., “Rabindranath Tagore–‘The Greatest of the Bauls of Bengal,'” Journal of Asian Studies, November 1959, pp. 33-51.

[30] Dutta, Krishna and Robinson, Andrew, Op. cit., p. 35

[31] Ibid., pg. 64.

[32] Tagore, Abanindranath, Jorasankor Dhare from Abanindra Rachanabali, Vol I, Prakash Bhavan Calcutta, 1975, p. 304.

[33] Tagore, Balendra, ‘Dillir Chitrashalika’, 1895, Acharya, A. and Som, S., Bangla Shilpa Samalochonar Dhara, Calcutta 1986, pgs. 72-82.

[34] There is some controversy on whether Abanindranath met Havell before painting the Krishna Lila. Abanindranath himself mentions showing these paintings to Charles Palmer, his teacher in watercolors and notes his positive reaction, but does not say anything about showing them to Havell. But there exists an undated letter from Abanindranath to Havell (Havell collection, Rabindra Bharati Archives, Shantiniketan) where he mentions working on a series of Geeta Govinda paintings. Few of the Krishna Lila series are specifically from the Geeta Govinda, but there does not exist any other set of Geeta Govinda paintings either. Hence it is very probable that this is the series he is announcing in the letter.

[35] Chakrabarty, Ramakanta, Vaishnavism in Bengal, Sanskrit Pustak Bhandar, Calcutta, 1985, pg. 349.

[36] Sanyal, Hitesranjan, “Trends of Change in the Bhakti Movement in Bengal,” Occassional Paper 76, Center for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta, 1985.

[37] Wulff, Donna M., Op. cit., pgs. 100, 110.

[38] I have located at least 25 such poets from a variety of Padabali sources. Here is a partial list: Sultan Nasir, Ainuddin, Afzal, Mohammad, Sayyad Murtaza (a prolific padakarta), Fazil Nasir, Sayyad Sultan, Sayyad Ainuddin, Nasir Mohammad (several padas under this name), Akbar Shah, Kamar Ali, Alaol, Fakir Habib, Najar Mohammad, Mir Faizullah, Mohammad Hasim, Pir Mohammad, Ibrahim Khan, Mirza kangali, Chand Razi, Salbeg, Sayyad Feroze Shah and Yashoraj Khan.

[39] Roger Fry’s indictment of the Bengal School – accepted by Coomaraswamy – on the ground of its being illustration, is an example of the uncritical continuation of this post-Renaissance prejudice. See Fry, Roger, ‘Oriental Art’, The Quarterly Review, vol 212, Nos. 422-3, Jan. – Apr. 1910, pg. 237.

[40] The use of the Bengali alphabet to write Sanskrit is common in Bengal, but for Abanindranath, schooled in Sanskrit College and well versed in the Devanagari script, this must be seen as a choice.

[41] See my discussion of brata in Chapter 3.

[42] This is at least the widely held view of the matter and among the chief distinctions between the Gaudiya amd Sahajiya forms of Bengal Viashnavism, though some debate also surrounds the issue. See Das , Rahul Peter, “Chaitanya’s Vaishnavism in Bengal: Some Enigmas” in Essays on Viashnavism in Bengal, Firma KLM Private Limited, Calcutta, 1997, pgs. 23-38.

[43] See, for example, Dipesh Chakrabarty’s discussion of this distinction in Bankimchandra, Rabindranath and Saratchandra Chattopadhyay in his chapter ‘Domestic Cruelty and the Birth of the Subject’ in Chakrabarty, Dipesh, Op. cit., pp. 135-141.

[44] See the discussion on Rabindranath Tagore in De, Esha Niyogi, “Decolonizing Universality: Postcolonial Theory and the Quandary of Ethical Agency” in Diacritics: A Review of Contemporary Criticism, Summer 2002, volume 32, no. 2, New York, p.42.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Deshpande, G.T., Abhinavagupta, Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi, 1989, 1992.

[47] For a concise introduction, see Dimock, Edward C., “Doctrine and Practice among the Vaisnavas of Bengal” in Singer, Milton ed., Krishna: Myths, Rites and Attitudes, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 1996, 1971, pgs. 41-63.

[48] Within the diverse usages of the Krishna Lila, the Abhisarika becomes a source of varied interpretation and doctrinal variation, as in debates on the spiritual preeminence of swakiya and parakiya prem. Ibid., pgs. 55-60.

[49] Kaho sakhi ki kori upay/Naiyer nabik hoiya e jauban chay/ paromad hoilo soi paromad hoilo/naiyer golar mala mor gole dilo/Je chilo kopale soi je chilo kopale/Nabik hoiya more paroshiya bole/kolonko hoilo soi kolonko hoilo/Bole chole naiya more kole kore nilo/Gyandas kohe dhoni na bhabo bisadh/Nander nondon naiya kiser paromad.

[50] Abanindranath later reminisces about a prominent bhadralok Vaishnav, Sisir Ghosh, editor of the swadeshi Bengali newspaper Amrita Bazaar Patrika, who complained upon seeing his paintings that they did not resemble the physical types of Radha and Krishna as described in Vaishnav literature. Tagore, Abanindranath, Jorashankor Dhare, Calcutta 1971, p.155.

[51] The notion of “worlding” is taken from Heidegger’s later works. See, for example, Heidegger, Martin, Poetry, Language, Thought, Albert Hofstadter trans., Harper & Row, New York, 1975, p. 180.

[52] See Dipesh Chakrabarty’s discussion of culturally mediated experiences of darshan and rasa in quotidian life in the chapter on ‘Nation and Imagination’ in Chakrabarty, Dipesh, Op. cit., pgs.163-79. Also 19th c. mystic Sri Ramakrishna’s description of samadhi at the sight of a British boy in tribhanga pose. See Yogeshananda, Swami compiled, The Visions of Sri Ramakrishna, Sri Ramakrishna Math, Madras, 1980, Pgs. 33-4.

[53] Srimad Bhagvata, trans, by Subbarau, S., Sri Vyasa Press, Tirupati, 1928, Skanda 10, Adhyaya 39, verses 19-20.

[54] Wulff, Donna M., Op. cit., p. 104.

[55] Wulff, Donna M., Op. cit., pgs. 99-111.

[56] Another form of “communitas” which based itself on the Krishna Lila and attained to an even greater popularity was the color-play of Holi or Dol.

[57] See, for example, Mitter, Partha, Op. cit., p.277.

[58] Wulff, Donna M., Op. cit., pg. 104.

[59] Dimock, Edward C., Op. cit.

[60] Sanyal, Hiteshranjan, Bangla Kirtoner Itihas (Bengali), Center for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta 1989, pgs 190-205.

[61] Wulff, Donna M., Op. cit., p. 101.