Debashish Banerji

This paper looks at three instances of art belonging to different periods of Indian history and attempts to draw out the role of the artist in the performative matrix of imperial power in each case. How does imperial power use art to authorize itself in each case? In what performances are such uses embedded? What is the nature and degree of the artist’s agency in each case? What are the continuities, changes, innovations in the structural temporality of each case? These are some of the questions raised by this paper in an attempt to reflect on the changing performative space and social persona of the artist in an imperial context and finally focus on the operation of this social agency within the colonial/national interchange of the early 20th c.

Rajya Mandala

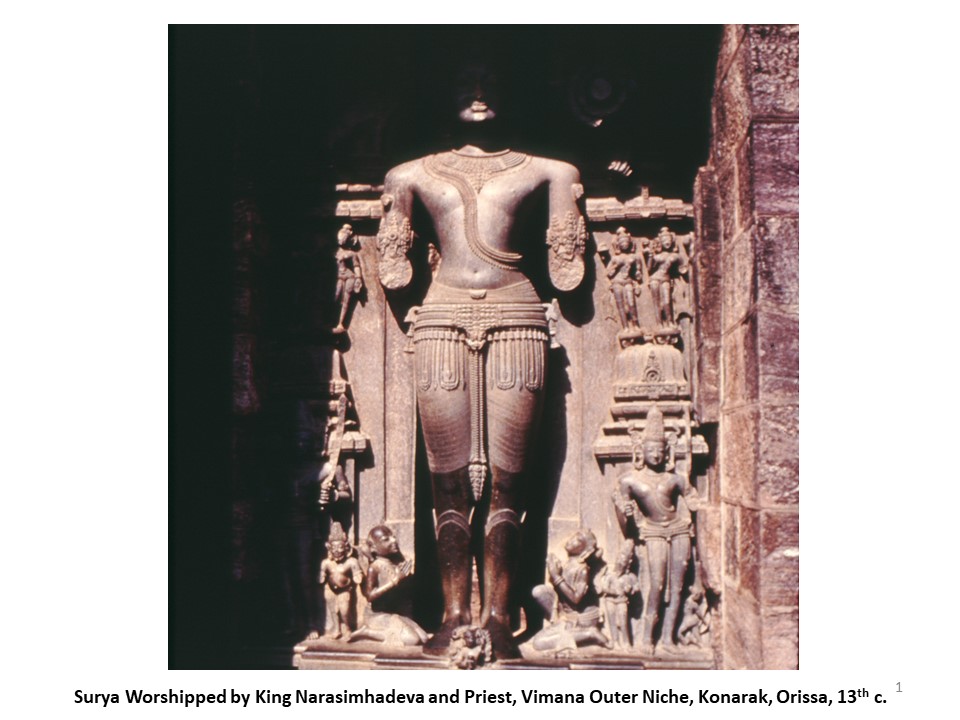

My first instance exemplifies medieval Hindu practices of imperial authorization through art. As a case, I draw attention to the images of the king Narasimhadeva at the sun temple at Konarak. The king is represented at the outer entrances to the vimana at the feet and to the right of the standing sun god as a worshipper (IMAGE 1). The same god image is flanked on the left side by a worshipping priest, the preceptor of the king.

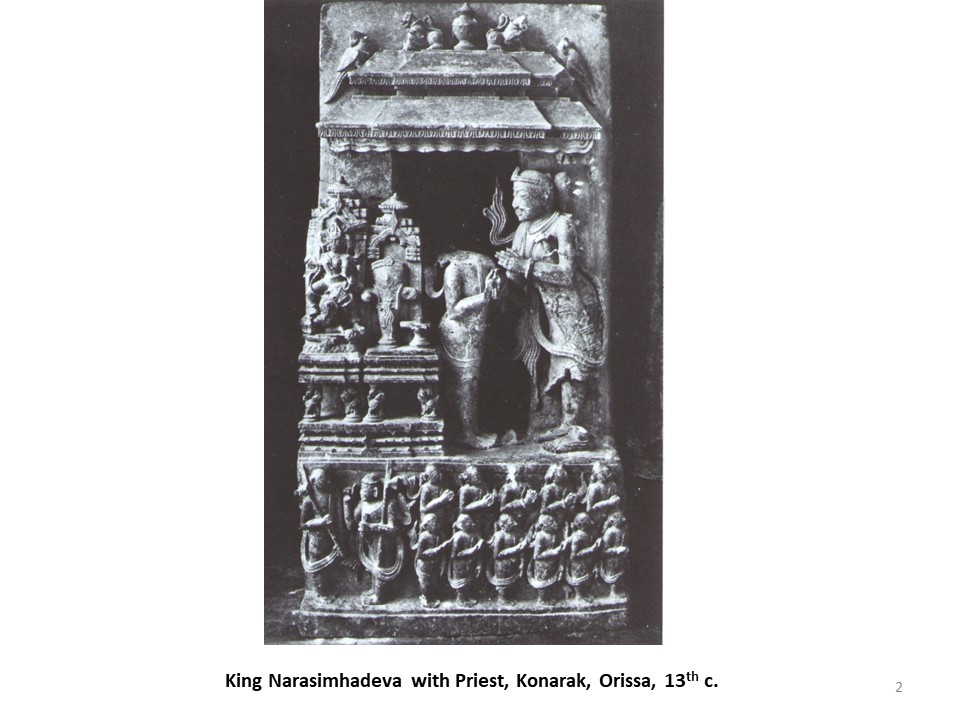

This tableau of god, priest and king is then repeated in the garbha griha in front of the now missing vigraha (deity-icon) but here the figures are related in a performative structure – the priest/preceptor in front of the deity and the king facing the preceptor and receiving the prasada of the inaugural puja from him (IMAGE 2).

Ronald Inden has done pioneering work in laying out the eristical performative space within which medieval Hindu kingship maintained its dynamic authority, using the Rashtrakuta kingdom of the Western Deccan as an example.[1] The construction of a temple and the ritual of power-transfer and royal-divine identification was part of this performance conducted within a knowledge-power matrix involving the mandala of competing and cooperating rulers and the organized vargas (classes/castes) of subject-citizens.

The temple to rival all temples – as in the case of the Rastrakuta king, Krishna III, Kailashnatha, the Lord of Kailash transposed with his mountain abode to the Deccan plains; in the case of Narasimhadeva, the sun god descended to earth with horse, chariot, charioteer and wives, for the conduct of his diurnal journeys – established the imperial authority of god and his replica-representative, the king, for all to see from as far as the eye could see and in an enduring form designed to outlast time, eternal. But this identity was nevertheless subject to the mutative powers of time, the field for the battles between devas and asuras, and needed repeated acts of power and consciousness to maintain itself dynamically as manifest dharma. At the center of this were abhisekha rituals, rituals of anointment representing both the adherence and worship of subject-citizens and the “descent”, avataran, of divine power, shakti into the constructions of time-born humans.

The abhisekha ritual was part of the process of puja whereby divine power was invoked first into the deity-icon and then, into the king by the Brahmin preceptor of the king and priest of the deity, who thus midwived the process of divine birth and transference in both cases. The puja to the deity resulted in the prasada or ucchista of the deity, the divine leavings, charged with divine power, which were first received by the king, thus seen as first or premier of the subject-citizens of the god as divine king, identified most closely in shakti and dharma with this divine in the social polity. It is this process that is represented in the tableaux of the garbha griha at Konarak. The prasada was subsequently distributed among the representatives of the different vargas (classes/castes), who were thus designated subsidiary subject-citizens of the same divine polity, thus also identified with the same shakti and dharma in maintaining their own professional and social duties in a dynamic and repeatedly re-enacted form under imperial leadership.

One of these vargas was the citrakara (artist), a relatively lower order or caste in the social construct. The citrakar was also a necessary midwife in the performative manifestation-space of this divine polity. Unrepresented except through his work, unknown by name except in the documentary records of sutradhars and the internal mythologies of this caste and its patrons, not socially adulated like the Brahman priest, he was nevertheless a primary agent in the materialization of the spiritual social space. Commissioned sometimes from a great distance for the construction of images, sought out often as war booty in the competitive performances of royal kingship, the citrakars developed their own canons, mythologies and oral and written rituals for art making that shared an overlapping reality with religious sastras and re-enacted in their own way the processes of bestowing divine power in material forms.

The agency of the citrakar varied, again eristically, in the field of cultural production[2] within this divine social polity. For example, the choice of representing the king and the forms of this representation in the sun-temple at Konarak may have been made by the king himself, by the royal priest, by some mediating minister or by the head citrakar, the sutradhar, or through relative negotiations between any or all of these, depending on specific instances of what Pierre Bourdieu calls cultural capital accumulation in the field of cultural production.[3] It is also important to note that what the citrakar authored and authorized here was not merely divine-royal authority within the public mandala of social polity but a specific creative instance of an impersonal canon of taste, a form of cultural identity, by which this royal authority proclaimed itself and its superiority to the constituents – competitors, cooperators and subject-citizens – of its mandala. That Konarak, in its splendid ruins, stands even today as a striking marker of originality within the cultural form of Ganga architecture and sculpture, is evidence of this power of authorizing civilization as an aspect of artistic agency in medieval Hindu India.

Rituals of Intimate Enjoyment

The second instance of art I would like to consider is a 17th c. painting from the court of the Mughal Badshah Jehangir (1569-1627), son of Akbar. Jehangir inherited his father’s court atelier, karkhana, and extended it with his own favored artists and interests. Born of Mughal and Hindu parentage, he also inherited an empire which functioned feudally in some ways like the mandala of medieval Hindu India, but with the major difference that eristical performances for the dynamic maintenance of power relations within this polity were not centered on the manifest image of a deity and rituals of the investment and identification of divine will in relative and functional degrees throughout the social polity. Operating within a hegemonic religious context of aniconic Islam, the holy book replaced the divine image or icon as source of social relations and laws in states with Islamic rule, though Jehangir’s father Akbar had devalued the Islamic orthodoxy and priest-jurists (ulemas) and the imperial formation included many Hindu kingdoms, where performances of Hindu rituals continued to mark internal investments and relations of power.

The co-existence of these domains in the imperial formation may be seen as a degree of secularization of the social polity with some of the characteristics of the public space of modern civil society. Indeed, we are dealing here with a time period contemporary with that of the Renaissance in Europe, and much has been written about the Renaissance input in the Mughal courts of Akbar, Jehangir and Shah Jehan. Portuguese traders and Jesuit missionaries were present in Akbar’s court and Dutch and British traders made their entry during Jehangir’s rulership. Apart from the matter of cultural taste, the most overt effect of this input can be thought of as an expanded objective awareness of the world, its size, shape, geography and the major imperial formations that ruled its territories. This enhanced knowledge has to be thought of as backgrounding the assumption of the royal name Jehangir (world-conqueror) by Akbar’s eldest son, Salim.

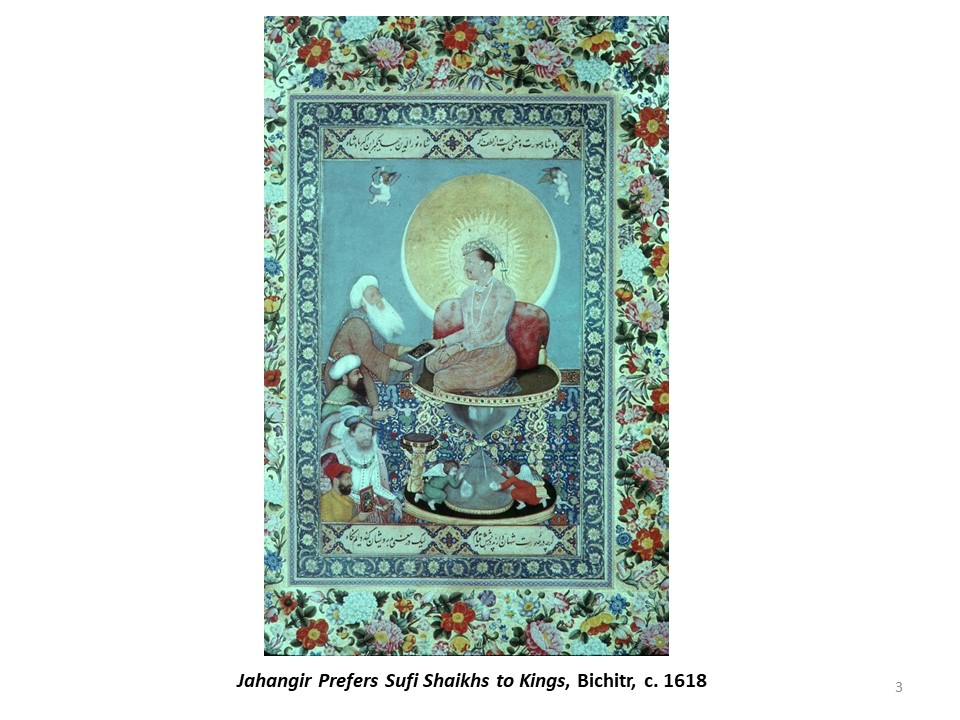

The Renaissance canon of naturalist art and the cultist authorial status of the signatured artist made its way into Akbar’s court and influenced the art of his karkhana. Iconic paintings of Queen Elizabeth I seen by Jehangir became the source of allegorical paintings painted for him by his artists, mainly Abul Hasan and his disciple, Bichitr. The painting for our consideration is one of the best-known of these paintings – Jehangir Prefers Sufi Shaikhs Over Kings, painted by Bichitr around 1618 and now at the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington DC (IMAGE 3).

The paintings of Jehangir’s karkhana have been seen as marked by personal idiosyncratic taste as against the historical and narrative interests of Akbar’s patronage and the painting for our consideration, along with its other family members of allegorical self-portraits of the emperor has generally been considered a full-blown expression of Jehangir’s megalomania. But what interests us here is the life of its content within the performative space of the maintenance and renewal of imperial authority through rituals of power in the royal court. Unlike the public rituals of medieval Hindu India, involving the entire social polity of the imperial formation, the quasi-secular space of Jehangir’s empire was better maintained through private courtly performances. Within the internal domain of the court, what might be called a liminal public-private domain, the messages of allegorical portraits circulated in albums, muraqqa, for the intimate viewing of courtiers – military generals, ministers and nobles and princes or other royal representatives of vassal courts. What was authorized in these acts of viewership was not only the status of the emperor as ruler of the imperial formation, a continued notion of the chakravartin of the rajya-mandala, but also a more enhanced and geo-politically informed image of world ruler, samrat. As in the medieval Hindu enactment, intimately and inextricably associated with this imperial message came the authorization of civilizational taste, cultural identity; but in keeping with the increased individualism of a quasi-secular and proto-modern social polity, this identity was less concerned with an impersonal canon of public taste than with the authorization of private imperial connoisseurship and authorial genius.

The painting in question quintessentially exemplifies these features. Here we find a middle-aged Jehangir in profile surrounded by an united sun and crescent halo, seated on an enormous hour-glass throne and either proffering or receiving a book from/to a bearded Sufi sheikh. Next to the sheikh and closer to the viewer are three other figures, respectively a likeness of the Ottoman sultan, of James I of Great Britain and of the artist Bichitr himself, holding a painting with animals in his hands. The Sufi sheikh has been identified as Shaikh Husain, a successor of Chisti saint, Salim of Fatehpur Sikri, after whom Jehangir was named. Two cherubs are seen in the sky above on two sides of Jehangir, one with a bow and the other shielding his eyes from the dazzling majesty of the king. Below, at the base of the hourglass, two more cherubs are busy inscribing a message of millennial longevity for the emperor.

The cosmic connotations of the portrait are unmistakable, though the lineage of divine authority is left ambiguous and does not base itself in a public ritual as in the medieval Hindu case, taking its root in the imagination instead. But as in the medieval Hindu case, it involves a transaction between the emperor and his spiritual guide in which divine power, here exemplified by the book, is exchanged. Is the badshah offering the book to the sheikh or is it the other way around? The picture is inscribed, “Though outwardly shahs stand before him, he fixes his gazes on dervishes”, but the badshah’s eyes are not focused on the dervish or on anyone or anything visible, but gaze ahead into infinity. Are these the eyes of the “realized man” of the Gita, to whom Brahmin, king and beggar are equal? The sheikh, on the other hand, looks up directly and adoringly at the badshah. The sheikh, in his reverence, does not touch the book, but receives (or offers) it on his shawl, here functioning as a wrapping cloth, whereas the badshah handles the book as one intimate with it.

What is the source of the badshah’s divine authority? If it is the book, the subtle signs would place him closer to it than the sheikh. Religious authority in conventional Islamic courts was the province of the priest-jurists, the ulemas, but the sheikh is not an ulema, nor is he a Sufi of the order that supported the ulemas, the Naqshbandis. The Chisti order, to which sheikh Husain belongs was marked by a synthetic eclecticism in religious matters, a turn towards heterodoxy and the prioritization of life as a vehicle of divine experience over the legal strictures of the holy book. Stuart Carey Welch suggests that it may be the autobiographical book of his life, the tuuzk-i-jehangiri which the badshah is offering as divine blessing to the sufi sheikh.[4] Thus a mysterious ambiguity marks the divine authority of the badshah in this painting – an ambiguity in keeping with the doxic unsettlement of the time[5] – is Jehangir born divine, is it by blood, through the divine lineage of Timur and Ginghiz, with which the Mughals from Babur to Akbar were so obsessed, that he acquires his divinity, is it through spiritual discipline or through “inspiration” or through spiritual transmission from the Sufis or their holy books? Thus the central transaction of the painting masks an eristical and negotiated divinity in the discursive and performative space of imperial authority.

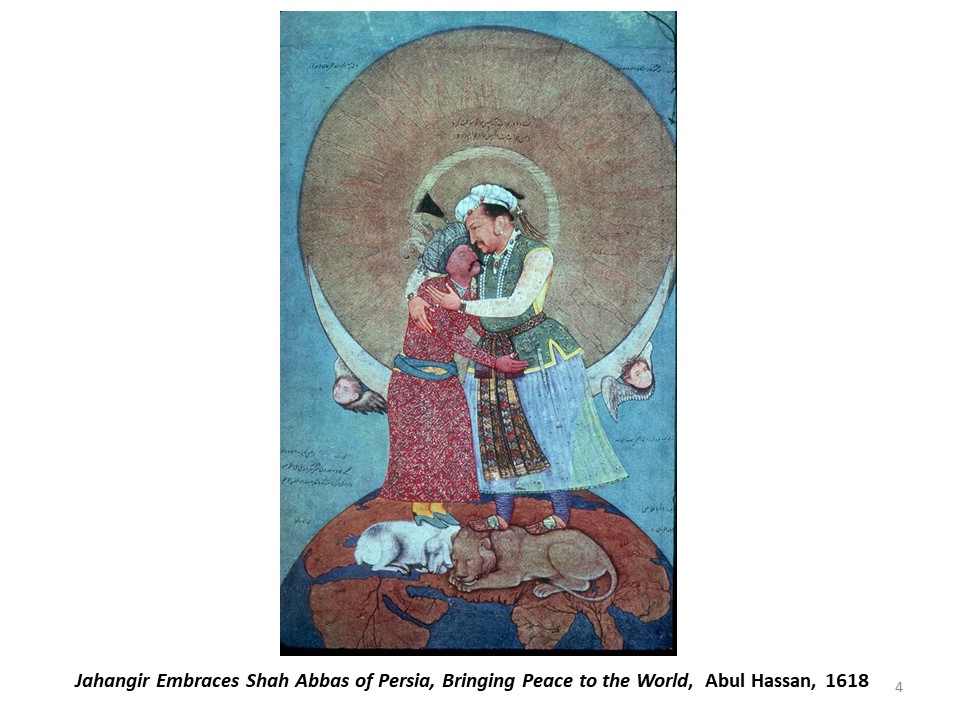

The Ottoman sultan and the king of Great Britian, stationed further away from the badshah, reference a global world order in which Jehangir, “world-conqueror” is paramount (samrat). This fantasy-reference is shared by a family of portraits, in several others of which the place of these two is taken by Safavid ruler Abbas I, Shah of Persia, whom a hieratically amplified Jehangir smothers in his expansive embrace (IMAGE 4).

Undoubtedly, these portraits were not for the eyes of these other “world-rulers,” but for the members of his own court and imperial formation – viziers, kotwals, generals, governors, administrators but particularly representatives and princes of vassal kingdoms – once more an eristical gesture of authority acknowledging the objectified world-knowledge of a discursive proto-modernity.

Also not to be lost to us as part of this new discursive space is the authorization of an authorial individuality resting on the “secular divinity” of creative inspiration. As mentioned above, the badshah himself, united with the solar-lunar origin of creation is the source of divine creativity on earth, the text of his life-story accepted as spiritual learning and blessing (baraka) by Sufis, creative influence flowing from his person into all his subject-citizens, inspiring them to acts of individual creativity. The artist, Bichitr is himself the example of such a subject, authorizing his own authorial status both through his signature and his brazen appearance in person in this cosmic circle ruled by Jehangir. Nominally representing the creative sphere, he authorizes thereby, as in the medieval Hindu case, the cultural identity and supremacy of Jehangir’s regime, but rooted now not so much in an impersonal canon as in connoisseurship and individual genius.

The eristical authorization of creative agency by the artist goes further than his self-inscription into the allegorical image. Through subtle disjunctures between image and text, the artist offers his critical commentary on the imperial person and regime. We have already noted one such instance of the play between image and text in the case of the relative status between badshah and sheikh. Here the creative mistranslation accrues to the benefit of the badshah, but perhaps such a reversal of role also prioritizes the power of secular creativity over that of spiritual piety and thus indirectly places the artist above the Sufi. The other instance occurs where the two cherubs are writing wishes of millenial longevity for the badshah but through the darkened hourglass the viewer sees the meager remaining quota of sand running into the lower chamber. The sands of Jehangir’s life are running out in this ironic and eristical subaltern comment by the artist Bichitr.[6]

The Delhi Durbar

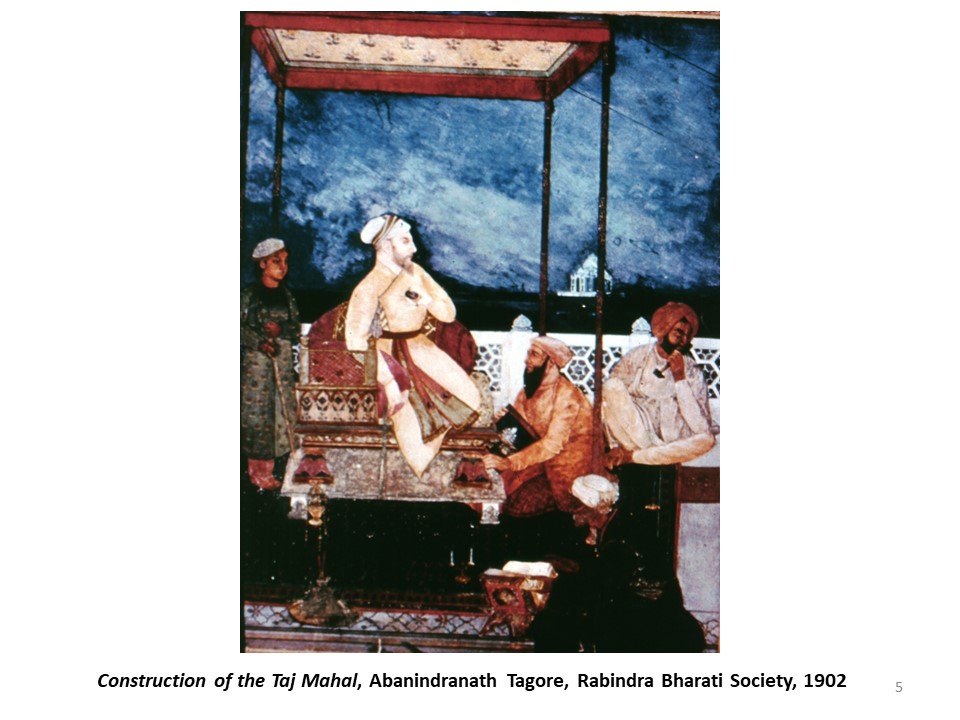

Our third example comes from the start of the 20th c., in an India under British colonial rule but from the hands of an Indian Bengali artist, Abanindranath Tagore. This painting subtly connects to the second painting of our choice in being about a Mughal badshah, the son and heir of Jehangir, Shah Jehan. The painting represents the Construction of the Taj Mahal, designated by Orientalist favor the eighth wonder of the world (IMAGE 5).

This painting was submitted along with two other Mughal-themed paintings for display at the exhibitions of the 1902-3 Delhi Durbar to commemorate the coronation of British king Edward VII as emperor of India. This spectacular event, masterminded by the Viceroy, Lord Curzon can trace its hybrid genealogy to British public coronation rituals and Hindu medieval ones, both concerned with the investment of divine authority in kings as a public performance eristically establishing the order of the social polity. However, unlike the pre-modern emphasis on divine authorization, Curzon’s commemoration had for the mythological source of its investment, western civilization with its teleological spearhead of universal modernity, a gift of technology and rationally systemic institutions assimilating into itself the “primitive” practices and paraphernalia of subject non-western peoples, seen as the static and eternal living museum and tourist preserve of Europe’s past.

There was no coronation ritual enacted here and the British emperor did not put in an appearance. Once again as in the medieval Hindu case, the spectacle was a major public one, involving all sectors of the entire population of India, united for the first time as a subject subcontinent within the world imperial formation of Great Britain. Within this all-inclusive performance of imperial power, our painting takes its place within the institutionalized secular public space of authorizing cultural excellence through competitions meant both to select for and example imperial authority and civilizational taste.

The source of divinity here has been displaced from the unitary deity of pre-modern Hinduism to slippery transactions between colonialist post-Enlightenment rational positivism and Orientalist romanticism, each with their own internal conflicts.[7] What is the authority invested in the emperor and emanating from him into the body-politic as the controlling and ordering principle of the imperial formation? Is it Universal Reason, the immanent divine property of the Enlightenment or is it Creative Inspiration, the romantic godhead of a post-Renaissance Orientalism?

The painting in question makes its appearance within this institutional space from a regional/local proto-nationalist cultural history of engagement with colonialism, today designated the Bengal Renaissance. This engagement, in the case of Abanindranath, is a creative choice of response to the inflected interpellation of British Orientalism, as brought to him through his close contact with E.B. Havell, principal of the Calcutta Govt. Art College and an Indophile follower of the Arts and Crafts Circle of William Morris. The painting shows Shah Jehan seated on a throne with a young girl, presumably his daughter Jahanara behind him and a bearded and turbaned man with a painting of the Taj in hand sitting on the ground directly in front and showing the emperor this object. Also seated on the ground, obliquely to the front and back of the emperor, respectively, are an old man reading from a book and a younger turbaned man with a chisel in hand, immersed in thought.

We find a number of elements in this painting which correspond with the allegorical portrait of Jehangir, but configured to other significances. Here too, the badshah looks straight ahead, as if lost in reverie. But it is not the ambiguous source of divinity that is in question here. The badshah wears no halo and handles no book. Instead, taking the place of the sufi is the architect of the Taj, design (naksha) in hand. The central transaction here does not involve a divine investiture, nor does it eristically establish the superiority of the badshah thereby in the circle of kings. Instead of the world rulers, what we find arrayed around Shah Jehan are the constituents of the field of cultural production – the patron surrounded by the architect, the craftsman, the canonical written tradition and the domain of subjective intimacy and inspiration.

Moreover, in comparison with Jehangir’s portrait, we may think of a double displacement here – the holy book is present, but has moved to a secondary place at the bottom of the painting; the artist, who was at the bottom of Jehangir’s painting with his handiwork has moved here to the position of imperial confidante, in closest communion with the badshah. It is a creativity which authors the marriage of rationality and romanticism, positivism and orientalism, here exemplified by the Taj which becomes the immanent divine principle bestowing authority on the emperor and through him on the subject constituents of his empire and their co-construction of the monument of civilizational taste.

In the secular modernity of the now undisputed public space of British imperialism, the artist Abanindranath may also be thought of as exercising his authorial agency through subtle creative displacements of authority based on an interpretive retelling of Havell’s famous line on the Taj: “The Taj Mahal belongs to India not to Islam.” [8] Is the badshah standing in for British imperial authority and the architect, Shah Isa from Havell’s telling, for the artist Abanindranath, their relationship made the primary eristical gesture, more important now than the wars of kings in authorizing empire?[9] This would seem to be the obvious reading, crafted for the consumption of the exhibition examiners as well as the procession of British authorities in this subcontinental performance of imperial authorization.

But if it is the principle of creativity that is the authorizing source, is not the badshah also an alter-ego for the primary agent, the artist? And is not the artist himself not a monolithic subject but a field of dialogic and eristical negotiations, made up internally of the constituents of the field of cultural production, here seen arrayed around the badshah?

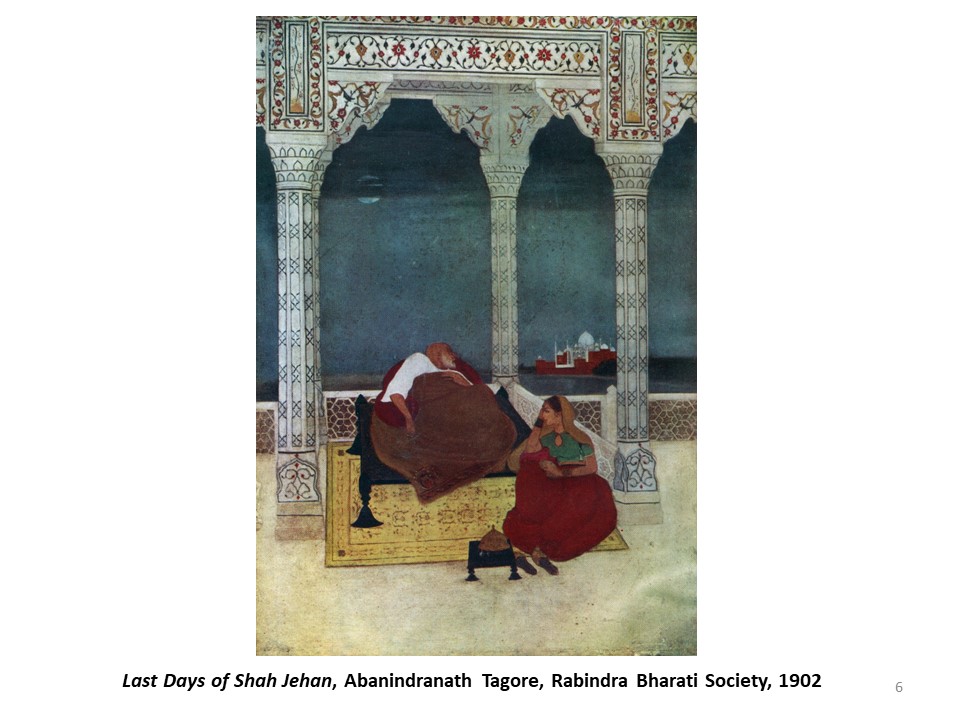

In Havell’s version, the Taj Mahal belongs to India, not Islam because it is the real-symbol of a hybrid civilization, Hindu and Muslim, traditional and innovative. In fact, the painting of our consideration cannot be taken in isolation but needs to be considered along with the two others he submitted for the exhibition and thus present simultaneously within the performative space – only one of which survives at present – The Last Days of Shah Jehan (IMAGE 6).

This painting shows the aged Shah Jehan, now imprisoned in the same pavilion of creation by his son Aurangzeb, with his eyes transfixed on the Taj. Taken with this painting the Construction of the Taj presents a thinly disguised allegory for the rise and fall of imperial authority but the endurance of the work of creation – produced not authorially but collaboratively by the hybrid constituents of the emerging nation.

From these three examples dealing with the place of art and artist in the performative field of imperial authorization, what emerges is the progressive visibility of the field of cultural production and the prioritization of civilization and creativity at the center of the eristical negotiation. Starting from a premodern maintenance of the symbolic unitary source of royal authority and the invisibility of the artist, we move to a proto-modern condition where the artist makes his appearance and the performative field is marked by an ambiguous eristical play between religious, political and creative power. This negotiated divinity still however vests itself in an unitary source – artist as authorial subject as a parallel to the unitary imperial authority of the king or of God. In the third case, we find a colonial/national eristical ambiguity inscribed into the performative field, a suggested transition from colonial/imperial to national/democratic authority and the emergence into full visibility of the field of cultural production in place of the rajya mandala of past representations. The authorial subject, mark of modernity, is ambiguously and suggestively doubled with the post-modern emergence of the negotiated field of civilizational authorship, here brought together under the hybrid patronage of imperial/national authority and casting the future trace of anarchistic utopia.

[1] Inden, Ronald. Imagining India. Cambridge, Ma: Blackwell, 1990, pp. 213-262.

[2] I have adapted here Pierre Bourdieu’s analysis of the “field of cultural production.” Bourdieu views the production of cultural goods in terms of power relations in a symbolic economy of social advantage. See Bourdieu, Pierre. The Field of Cultural Production. New York: Columbia University Press 1993, pp. 29-144.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Welch, Stuart Cary. Imperial Mughal Painting. New York: George Braziller, 1978, p. 82.

[5] My use of the term “doxa” here also follows Pierre Bourdieu, for whom it refers to the unquestioned and unarticulated assumptions of a society, fossilized into its cultural practices, so as to be beyond choice or alternative. During periods of intense culture contact, a society’s doxa often stand exposed as arbitrary, leading to “doxic unsettlement.” See Bourdieu, Pierre. Chapter on ‘Doxa, Orthodoxy, Heterodoxy,’ Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977. pp. 159-171.

[6] Welch, Op. cit.

[7] Enlightenment positivism, “the white man’s burden,” was riven with the ambiguity of whether non-white peoples were fully human, candidates for the gift of rationality or racially inferior species. Orientalist interest, similarly suffered from the dichotomy of treating non-western cultures as stereotyped preserves of museology and tourism [vide Edwarrd Said], or of seeing them as domains of cultural interchange. See Banerji, Debashish. “The Orientalism of E.B. Havell”, Third Text. London: Routledge, Vol. 16, Issue 1, 2002, pp. 53-6.

[8] Havell, E.B., Indian Architecture, London, 1927, p.24. Though Havell’s pithy statement on the Taj occurs in this text much after Abanindranath’s Shah Jahan paintings, Havell’s art historical ideas were already well developed during his tenure at the Calcutta Government Art College and Abanindranath could hardly have been unfamiliar with them.

[9] Havell, Op. cit., , p. 24-7, 84