Debashish B anerji

Ananda Coomaraswamy has often been called the father of Indian art history, but it is E.B. Havell who much more properly deserves that title. Havell was a teacher from the Central School of Industrial Art at South Kensington, London, which was directed by Henry Cole and founded as an effect of criticism of British handicrafts at the Great Exhibition of London of 1851. The group that launched this criticism included figures such as Henry Cole, Owen Jones, William Morris and George Birdwood, men who traced their ideological descent from the neo-Gothic propensities of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and its succeeding avatar, the Arts and Crafts movement. Resisting the flattening of taste and the disintegration of community and its homely enjoyments due to the determining regime of the Machine with its mass production and commodification of human life and relations, these thinkers sought to stem the declining standards of British crafts and looked for revitalization to the living craft traditions of ‘non-western’ regions, such as India. But though this group defended Indian crafts and sought to influence government policy regarding art education in India, they retained an ambivalence towards the status of Indian art. Their general lack of comprehension in this matter followed after the opinion of John Ruskin, one of the ideological founders of the neo-Gothic and Pre-Raphaelite movements: “[The Indian] will not draw a form of nature but an amalgamation of monstrous objects” [Mitter1, 245] and pronounced most explicitly by Sir George Birdwood: “Painting and sculpture as fine arts did not exist in India [Mitter1, 269].” Of this following, only Havell could apply William Morris’ Arts and Crafts anti-Renaissance ideals towards the formulation of an alternate classicism with its center in India. As pointed out in the Introduction, the Arts and Crafts transposition of western art history relocated its zenith from the Renaissance to the Middle Ages, prioritizing their idealist and collective art practices and communitarian integration of art, craft and environment over the privileging of ‘the fine arts’ and the artist as sovereign subject and of art enjoyment as an elite act of connoisseurship in contextless galleries as initiated in the Renaissance and carried into the present. In India Havell discovered an idealist/spiritual and integrated art making tradition similar to that of the Middle Ages but with a greater vitality and a clearly articulated canonical discourse which allowed it to last almost into the present and which was in threat of being destroyed by the Raj. He saw the origins of this canonical discourse in the Gupta period of the 5th c., and located the notion of a “classical Indian art” in that period.

The problem remained of course of how such a Hindu/Buddhist (read “Aryan” by Havell) origin of classicism would accommodate the close to five hundred years of Islamic hegemony in India. Though it was true that the Hindu architectural and sculptural traditions were severely retarded and supplanted during the period of Muslim rule, Havell saw them live on in the arts and crafts of Islamic India. Apart from the fact of continuities in the artisan families and their teaching methods and designs, Havell located the source of such continuity in pan-Indian ideologemes that had established themselves into the social imaginary and the political habitus of India and which several Muslim rulers, particularly the Mughals, accepted and adapted to their own purposes. One of these ideologemes was the notion of the chakravartin or “universal ruler” who united the known world of India with all its peoples and cultures. Ronald Inden in his “Imagining India” makes a similar point about the pan-Indian acceptance of ideologemes such as chakravartin and utilizes it as one of the cornerstones in his theoretical study of the Rashtrakuta empire under Krishna III. He points to the collective ownership of concepts such as these, formed historically, discursively and through intersubjective practice : “The idea of the chakravartin, of a universal monarch, and with it the idea of their “sovereignty” or rather, overlordship over the earth, was a whole to be embodied in one polity (and not a particular to be instantiated in independent, sovereign nation-states) appeared before the time of the Mauryas. Buddhists, Smarta Brahmans, Saivas and Vaishnavas, as well as the Jainas dialectically shaped and reshaped political theologies of the chakravartin from that time on. That is, all of the major religious orders incorporated into their soteriologies the idea of a universal monarch or paramount king of India, a ‘great man’ (mahapurusha) who, endowed with special powers, was able to complete a ‘conquest of the quarters’ of India in the name of a still greater agent, the one taken as overlord of the cosmos.”[1] Havell does not develop his idea of the persistence of such ideologemes theoretically as Inden does so it is not clear if the chakravartin is for him an Orientalist essence which “manifests” occultly in some rulers or whether a history of intersubjective discourse is what he has in mind. But he sees the Mughal emperor Akbar as a chakravartin, uniting in his person and his policies the different social and religious discourses of India.[2] There is of course, the other question of whether Akbar saw himself as a chakravartin or it is Havell’s own Orientalist coronation, but it opens interesting possibilities of interpretation in the understanding of Indian art and identity which feed some of the ambiguities of Abanindranath’s paintings. In a similar vein, Havell makes his famous proclamation regarding the Taj Mahal, Shah Jahan’s architectural commission: “The Taj belongs to India, not to Islam.”[3] A statement of this kind opens itself immediately to the charge of “inclusivism”, a term coined by the Indologist Paul Hacker to refer to a hegemonic religion’s absorption of other religions through a suppression of differences.[4] I have dealt with Havell’s Aryanism elsewhere,[5] pointing out that it is less a racial than a cultural characterization and his bestowal of the title of chakravartin on Akbar may questionably be read as an Aryanization of the Moghuls all the better to justify the claim of the British as the next rulers of India. Havell does repeat an imperialist return-of-the-Aryan claim in several texts though the cultural hierarchy becomes reversed in his case with the “British Aryan” having much to learn culturally and spiritually from the “Indian Aryan.” This discussion is relevant to the shaping influence of Havell on the art of Abanindranath as I will later consider Abanindranath’s interpretation of Havell’s Indian art history in his own nationalistic art.

Thus, one may see Havell’s subjective interest in the formulation of an Indian art history as resting on (1) a desire to displace/revise the normative structure of a classical art history and (2) an imperialistic cultural Aryanism, which nevertheless credited the “Indian Aryan” with spiritual superiority. Apart from this relocation of Indian art and its history, Havell’s interest in the arts and crafts of India lay in the direction of a revitalization program stemming from an Arts and Crafts ideology. This he wished to attempt (1) through a revision of British art education and art patronage policy in India, so as to promote a living but unsupported tradition in Indian arts and crafts and (2) a revision of modern Indian taste and style, leading to indigenous and integrated/communitarian solutions to modern needs in design, architecture, arts and crafts.

Havell came to India in 1884 as the Superintendent of the Madras School of Art and a reporter to the colonial government on the state of art and industry. In 1896, he was appointed Principal of the Calcutta Art School and keeper of the attached Calcutta art gallery. Here Havell found the freedom to introduce radical changes in Indian art education and discovered a native collaborator in Abanindranath Tagore, whom he brought in as the Vice Principal of the art school and who along with his students became the center of a new ‘Indian’ school of art. The improbable meeting of Havell and Abanindranath was another happenstance of the Jorasanko family with its culturally stratified community. As touched on in the Introduction, at one end of the cultural spectrum of this extended family was the ritually bound orthodoxy of village sociality defensively cloistered against the presence of modernity; at the other end were a variety of progressive and heterodox approaches and lifestyles engaged in the creative and transformative hermeneutics of bridging modern and pre-modern worlds. The orthodox elements of the house were generally constituted by the “Jessore wives”, village girls from the Tagores’ ancestral home who were brought into the house after marriage and the servants and maids and other poor relatives who came to stay temporarily or permanently from the village. This section screened itself off from the outside world in the interiority of women’s and servants’ quarters. The intersubjectivity of the Jorasanko community included a fundamental acceptance of this diversity and strategies of relational negotiation within this acceptance. By Abanindranath’s childhood, the two major wings of the house had been divided so as to represent a religious split in the family – one wing, housed the large number of descendents of Dwarkanath’s eldest son, Debendranath Tagore, who had become a Brahmo while in the other wing stayed the original Hindu branch of the family, including Abanindranath and his two brothers. Debendranath’s eldest son, Satyendranath took the British civil service examinations and became the first Indian I.C.S. in British India. His wife, Gyanadanandini Debi, though also from a Jessore village, made herself literate and was outgoing and accompanied her husband in his social engagements with British administrators and foreign diplomats. Though with one foot in Jorasanko, Satyendranath, who was often stationed out of town, also rented accommodations in the “white quarters” of Calcutta and provided a forum for selective interchanges between white and bhadralok (specially Jorasanko) society. Towards this end, Gyanadanandini Debi was an active presence encouraging members of the Jorasanko household to form liaisons with the ‘foreign’ harbingers of modernity. Her own approach to modernity was not imitative, but consisted in a creative revision of domestic taste (particularly dress) which styled everyday culture into forms which would translate to both white and bhadralok society as “fashionable.” She actively disseminated these “fashionable” styles and behaviors among the women of the Jorasanko (and more extended bhadralok) community who were open to her, encouraging them also to engage through literacy and expression with modern ideas. Women of the family who were open to this encouragement learnt English, piano and embroidery from British lady teachers and traveled out of the home in horse carriages. This encouragement she also extended to the younger men of the family, her patronage to Jyotirindranath and Rabindranath, two of Satyendranath’s brothers, being well documented. She also started a house journal, Balak, for the children of the Jorasanko house. It was she who also encouraged Abanindranath to pursue art as a form of self-expression and set up the meeting between him and Havell, which would prove to be fateful.[6] This meeting in 1896/7, opened up a series of interchanges between the two, where Havell discovered a native collaborator whose ideas and art practice already showed a tendency in the direction of his own ideas for the revaluation of modern Indian art and Abanindranath found a teacher in the systematic modern “science” of Indian art history, to provide an orientation to his own art practice. One may identify Abanindranath’s point of departure as an artist as his Krishna Lila paintings of 1896/7, where he made a number of selective choices wresting the practice of art from its subjection to western academic illusionism towards a translation in visual terms of a communitarian strand of the regional movement known as the Bengal Renaissance. As forms of departure here, one may highlight (1) the miniature intimate format of the painting; (2) the communitarian and performative semantic field within which the paintings operate; (3) the regional hybridity of the paintings referring to a dialogic intersubjectivity; and (4) Abanindranath’s performative disclosure of the late Mughal Delhi school and the late Victorian or post-pre-Raphaelite style of text as the dual formative influences on these paintings. In this context, one may also point to the endemic problem of cultural nationalism which seeks freedom from colonialism but orchestrates bondage through the fossilized myths of the nation-state which it organizes. A nationalist art history is less equivocal about the collective unities it constructs, basing these on the notion of a racial or cultural essence. Abanindranath showed Havell these paintings and Havell was impressed by them. It is not difficult to see how certain features of the series would appeal to Havell as fertile possibilities for a revised modern ‘national’ art in alignment with his notion of an Indian art history but how also certain concerns of these paintings might pass him by.

In the interaction between Havell and Abanindranath, it is important to establish what constituted the “Indian-ness” of art in either case and to what extent Abanindranth reproduced the “national” construction of Havell. Havell’s attempt to induct Abanindranath into the art school as its vice-principal was met with resistance on both sides. He had to bend the official qualifying rules to appoint Abanindranath to the position of vice principal and Abanindranath refused to conform to the clock time of a teaching schedule and insisted on smoking his hookah in the classroom, thus occupying the space-time of the institutional productivity of academic knowledge workers with the alternate habitus of communitarian art practice. Havell was accepting of these practices and introduced innovations of his own to the teaching program which he felt reproduced ‘Indian’ methods of art pedagogy. For example, he abolished the “antique” class and replaced it with a process of meditation/introspection so as to create a mind-image of what was to be represented.[7] This brings to light a problem of relative framing in the Orientalist-nationalist interchange between Havell and Abanindranath, symptomatic of their difference. While Abanindranath attempted to pollute the aura of modern institutional discipline with the agora of the communitarian, Havell reframed Abanindranath’s practice in ahistorical Orientalist terms, as the conditions for the alternate discipline of making “Indian art.”

Havell also replaced the European copies of painting and statuary in the collection of the school and replaced these with Indian originals. It was on being shown one of these paintings, that of a stork by the Jahangir-period artist, Mansur, through a magnifying glass by Havell, that Abanindranath remarked that he was unaware until then of “the embarrassment of riches” that “our art” contained.[8] This reminiscence by Abanindranath is interesting, given the fact that he also recounts the long hours Havell spent with

him behind closed doors “explaining” the details of “Hindu art and sculpture” to him.[9] Havell, in his many tomes on Indian art, architecture and sculpture, did not have much to say about Mughal painting, and Coomaraswamy, who followed in the wake of Havell in constructing an Indian art history, ended his History of Indian and Indonesian Art with Rajput painting, refusing to recognize the entire corpus of art under Islamic rulership as Indian. In Havell’s case, as mentioned above, Mughal art received conditional entry as Indian art, after due Aryanization. For Havell, the classical center of “Indian art” was the Hindu and Buddhist art of the Gupta period. Though, after his contact with Havell, Abanindranath did make a few paintings on Hindu and Buddhist religious themes, these do not betray much influence of the classical canons, nor are they numerically conspicuous, either at this early phase or in his later artistic production. In fact, a curious ambiguity towards the gods and the devout evidences itself in his art. Admittedly, most of the “classical tradition” Havell spent his efforts establishing, was sculptural and architectural, but even the instance of Ajanta, lone example of Gupta/Vakataka classical fresco painting, failed to attract Abanindranath sufficiently so as to inspire in him the desire to visit these caves, though he helped make it possible for his students to travel there. Partha Mitter has pointed out how Havell’s ideas for integrated environments made him seek for commissions where art, architecture and sculpture would function together, but Abanindranth was not temperamentally suited to this kind of monumental art.[10] Thus what seems to have attracted Abanindranath in “Indian art” was the intimacy of relationship implied in miniature painting and the aesthetic pleasure of selective realism in Mughal miniatures – a realism not of surfaces (as in academic illusionism) but of impressions. R. Siva Kumar draws attention to “this common thread of realism” which attracted him in the three most prominent artistic cultures that were influential for him – British watercolor painting, Mughal miniatures and Japanese painting. In his words, “Abanindranath moved from a normative realism seen as tool for objective representation towards a freer naturalism permeated by subjective vision.”[11] Mughal realism was quite different from the idealized forms of classical Hindu/Buddhist art, including the illustrations of religious texts in Rajput and Pahari miniatures (though it is true that the latter, under the influence of Mughal painting, do show an eye for detail, in their depictions of natural surroundings and of portraiture). A typal anonymity of form is never present in the paintings of Abanindranath, even his gods and mythical beings expressive of personal individuality. This realism grounds the ahistorical ideality of nationalism in a memorable structure in local space-time, particularly since the figures, even in his mythical/historical paintings were often portraits of friends, acquaintances, members of the Jorasanko family or faces seen on Calcutta’s streets. This feature has led to the characterization of Abanindranath as a Baudelarian flaneur, by critics such as R. Siva Kumar.

Abanindranath’s “national art” then, can hardly be shown to draw its “identity” from the forms of classical Indian art, as defined by Havell. But Abanindranath conditions his appreciation of Mansur’s crane by saying that though marvelous, it lacked in “feeling”, which is what he was determined to supply in his own depictions.[12] Abanindranath’s training at the Sanskrit College in Calcutta as well as his exposure to “literary classicism” through his uncle Rabindranath and other Bengal Reniassance sources may come in handy here in arriving at a genealogy of “feeling” in his mind. The same classical period in art construed by Havell had been claimed for a notion of literary classicism by figures of the Bengal Renaissance, following German romantics and Orientalists such as Goethe and others. Paramount in the imagination of the literary classicism of the Gupta period was the figure of Kalidasa, whose poems and plays were widely believed to be steeped in the rasa aesthetics of Bharata. In thinking of Abanindramnath’s Krihsna Lila paintings, one needs to take into account the ontology of the rasa structure and its dissemination and assimilation through history and regionality, including the adaptations of the Gaudiya Vaishnavas and finally, its utility in the isolation of a “body of feelings” in the cultural nationalism of the Bengal Renaissance. Thus Mughal miniatures and rasa aesthetics seem to form the synthetic and stylistic core of the selective “Indianness” of Abanindranath’s ‘national’ art. Moreover, here too, as indicated in my discussion regarding realism and the body of feelings, the borrowing of historical bases to construct a ‘national’ art have other cultural and ontological effects relating to personal and regional histories and grounded in an internal communitarian reality, so that the ahistorical and archetypical nation referenced by these paintings slips into the intersubjective domain of participatory co-creation and the multiple meanings of open-ended re-creation.

Apart from these stylistic borrowings, Abanindranath’s nationalism in art, particularly of this early period, has been construed as a historicism by Partha Mitter[13] and as the projection of an Orientalist spiritual Other of the “materialist West” by Tapati Guha-Thakurta. What Heidegger has termed “the Europeanization of the world” is an epistemological and ontological teleology that will of necessity meet with a variety of strategies of resistance at home and abroad. Havell’s construction of an Indian art history, following his anti-materialist bias in the prioritization of the Middle Ages in Europe, could possibly be seen as a spiritual Other of a materialist Europe, though this too is debatable. But the word “spiritual” translates into a variety of specific practices with their divergent goals in the Indian lived context, and the division between “material” and “spiritual” in everyday life can hardly be distinguished, lacking any social history prior to British colonization. So even if we admit that the nationalist is interpellated by the Orientalist as the spiritual Other of a materialist Europe, thus framing and fixing the boundaries of the discourse, the agency of the nationalist can hardly be seen as determined and the genealogy and archaeology of meanings and the variety of discourses within which these are embedded need to be carefully examined to arrive at the semantic field generated by the response of the nationalist. This is particularly so in the case of Abanindranath. Guha-Thakurta completely ignores the complex intersubjectivity within which Abanindranath’s paintings are embedded, making the assumption at the outset of a reified spiritual Orientalism in his constitution of a “new Indian art”, and thus succeeds herself in reifying his practice. Regarding the historicism of Abanindranath’s paintings, particularly the paintings done under Havell’s influence and before his contact with Okakura Kakuzo, can be divided into a few mythological paintings, paintings from ‘classical’ texts, a few paintings from the life of the Buddha and paintings of events in Mughal history. If one is to seek the locus of Abanindranath’s nationalism, his historicism can be seen as nostalgia for a greatness that has passed. It is this that Shivaji Panikkar, Preetha Nair and Anshuman Das Gupta isolate as the essentialism of Abanindranath’s nationalism in their paper on ‘Art, Subjectivity and Ideology: Colonial and Post-Independent India.’[14] As in the case of their Orientalism, though there is no doubt some truth to this, and in fact, an amplification of the melancholic saturation in many cases after the meeting with Okakura and his Japanese artists, it is important to investigate the paintings for the marks of their intersubjetivity, to read them in their multivocality and recognize the different forms of address coded into them.

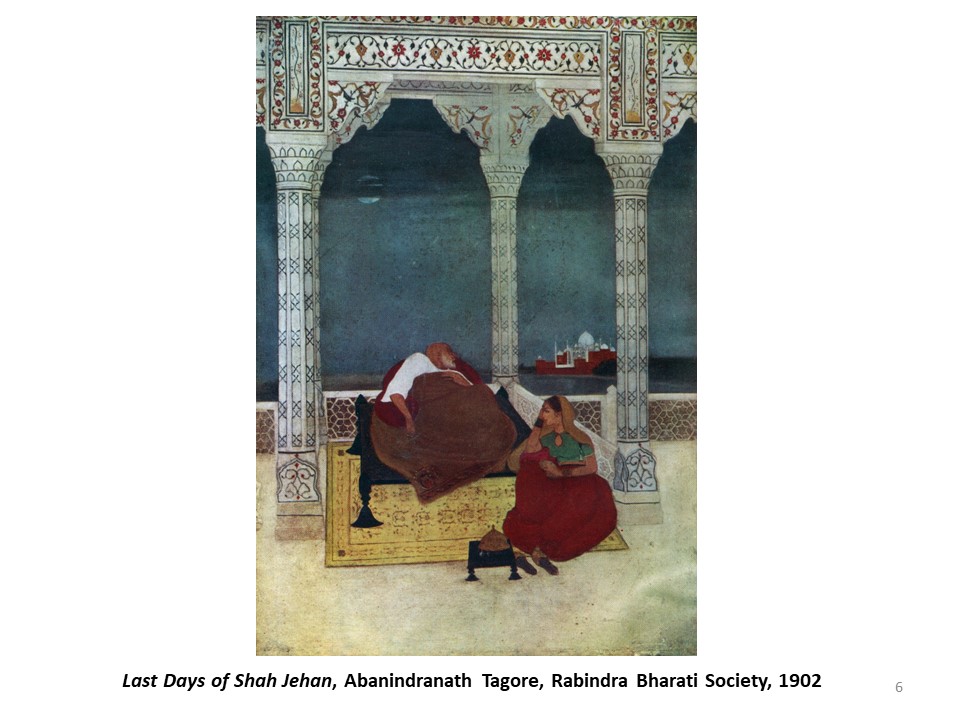

For example, two of the paintings of the post-Havell period in which Abanindranath seems to have invested a lot of attention concern the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan and his commemorative mausoleum to his wife, the Taj Mahal. These are ‘The Building of the Taj’ and ‘The Last Days of Shah Jahan’, both done in 1900-01 and presented at the Delhi Durbar of 1903, an event to mark the

The Building of the Taj/Abanindranath Tagore (Rabindra Bharati Society, Kolkata)

coronation of Edward VII as emperor of India. The paintings, along with another one by him on a Mughal theme, The ‘Capture of Bahadur Shah’, were displayed in an exhibition at the Durbar, in which the ‘Last Days of Shah Jahan’ was awarded a silver medal. If we are to take these paintings as carriers of nationalism, we must first acknowledge Abanindranath’s location of the national as not restricted to the Hindu past, but in some way including Islam. Of course, the caveat here is Havell’s assignment of ‘Aryan’ cultural qualities to the Mughals and his famous statement “The Taj Mahal belongs to India, not to Islam”, which Abanindranath was no doubt familiar with. Moreover, the Taj Mahal had passed into the romantic western Orientalist imagination as a wonder of the world, and thus an ‘Indian’ monument of far greater popularity than any Hindu monument of India (as is the case even today). So

Abanindranath’s identification of the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan and Taj Mahal as emblems of the nation would in some way speak much more strategically to the European or European-trained viewer. (This in itself hints at Abanindranath’s national essentialism as being not an invested but a strategic essentialism). Also, the fact of the Mughals’ being the last imperial national dynasty prior to the British, would be meant to have some effect, particularly considering that one of the paintings explicitly featured the act of imprisonment of the last Mughal emperor (Bahadur Shah) by the British. Seen in this light, the three paintings, taken together, immediately awaken the sense of a thinly disguised allegory on national subjection. ‘The Building of the Taj’ captures a moment of the glory of national creativity, when the wonder that was the Taj was built. I will consider this painting in greater detail so that its nuances and ambiguities can be better articulated. ‘The Imprisonment of Bahadur Khan’ presents the explicit subjection of the nation to British rule and awakens the memory of the 1857 Sepoy Mutiny, first war of Indian independence, when Bahadur Shah was nominally recognized by the renegade sepoys as the ‘emperor of India’, a title being assumed for himself at this very durbar by the British emperor. And ‘The Last Days of Shah Jahan’ are emblematic of the nation under British subjection – its native powers grown old, feeble and dying, gazing on the eternal glory of its own past creation with nostalgia, while attended on by a faithful helpless daughter. It is the third and last painting of the set which distills Abanindranath’s most characteristic saturated emotion, that of pathos, which while referring to a specific event in the life of a past emperor, extends itself into universality – the pathos of the past becomes the pathos of the passing, the present continuous, not merely of the nation, but of all nations, all empires, of the age, and of Time itself. Thus, to the British viewer, this allegorical pathos, combined with the realization of the Mughals as a “foreign” imperial power in India, once thought invincible, could awaken the anxious specters of alternate meanings – the rise, subjection and death of all imperial formations, including the invincible British empire, the empire over which the sun never set, with only its monuments of art left by Time as its trace. With the explicit referent of the Sepoy war behind and the simmering discontent which was to erupt as the Swadeshi movement in Bengal in a few years (1905), such a subconscious anxiety is not impossible to imagine as part of the imitational hybridity [vide Bhabha] of the paintings. Stylistically, too, the paintings were a thin hybrid graft of Mughal mixed perspective on British watercolor technique. Partha Mitter characterizes it as a “half-hearted modification of European linear perspective to accommodate the Mughal idiom.”[15] This would add credence to my view regarding the destabilizing spectral effects of the series, seen in terms of Homi Bhabha’s mimicry.

The metaphoric overtones of the pathos of “passing” in the ‘Last Days of Shah Jahan’ do not end here however. Painted in 1901, they carry the fin-de-siecle melancholy of the end of an Age [Siva Kumar], the passing of the pre-modern and the arrival of the modern. Fin-de-siecle nostalgia has been read as decadent and reactionary, since it longs for the stability of the past and resists the future. In this case, it may be said that it intuits the disappearance of imperial or oligarchic hierarchy and elitism and mourns this instead of embracing the democracy it will give way to. But such an evaluation presupposes a modernist teleology, and the necessary good of the fragmentation of society and the production of the isolated subject of modernity circumscribed by the global discourse of capital. Instead, the mourning for the passing of a pre-modern past may also be a yearning for a future where this past is reborn in a less flawed incarnation, a disjunction from the modern to the post-modern. This, indeed, is the concern with the communitarian that we find in a variety of turn-of-the-century cultural movements faced with modernity as an inexorable and imminent global phenomenon, from the Arts and Crafts movement in Britain to the communitarian streak of the Bengal Renaissance. But fin-de-siecle decadence hardly puts us in contact with the communitarian. Instead it may be thought of as a hyper-individualistic aestheticism and elitism, the illusory assumption of the sovereign subject of modernity. While it is true that the illusory sovereignty of the modern and the hierarchy of the pre-modern haunt this series of paintings, they point to a different time-consciousness in which the initiating image of the ‘Building of the Taj’ spirals repeatedly into place beyond the ‘Last Days of Shah Jahan’ initiating a new order of being and creation. This because the pathos of this last painting, traveling beyond the passing of an age, distills the sadness of temporality itself, the inescapability of the passage of Time, against whose destruction, only the transcendence of the creative work of art and the creative consciousness can stand. Indeed, we realize that Shah Jahan’s last days are not merely a meditation on the passing of the Mughal empire or of a pre-modern or pre-colonial India, nor the passing of all empire or of an age, but the mortality of time, which, as all Orientalists knew, Shah Jahan encountered early in his life with the death of his beloved wife and whose death he defied for all time with the creation of the Taj. Now, in his last days, the rapid steps of fleeting Time grip once more his contemplation, and with the imminent approach of their limit condition, he perceives once more, the incandescent structure of eternity in the hours and relives, with his gaze fixed on the Taj, his participation in that eternity. He is thus propelled out of pathos, out of time into the perpetual hour of the resurrection which re-instantiates the initiating conditions of the ‘Building of the Taj’. Now however, at his moment of subjection, the disillusionment of his sovereignty through imprisonment and his reduction to anonymity by time/death, the image is inflected slightly differently. Instead of the sovereign subject (literally, sovereign/emperor) of modernist art creation, we discover a field of art production [vide Bourdieu] with participants in a co-creative community – the sponsor, the architect, the artisan, the text and the realm of desire and intimacy. The specifics in the image are instructive. They show us the pre-modern conditions of hierarchic communitarian art production – there is Shah Jahan, the transcendental subject of national art production, determining through sponsorship the choices of architect and artisan, and faithful abider of the sacred text. Behind him stands his daughter Jahanara, reminding of the subjective domain of familial intimacy which purports to be the affective link awaking memory (daughter/mother) and relating time to the timeless. She will return to sit behind the downsized emperor (now imprisoned discard) in his last days, linking the moment of creation to that of passing. At this passing of an age, the sovereign/emperor/creator/subject has been reduced to commoner and in his return to the resurrected future hour of creation, the pre-modern power relations have been rendered unstable, but the communitarian field of production remains the same – the nation as enduring monument in the field of passing time is not the modernist project of democratic autonomy but the co-creative communitarian project of affective relations, and professional skills of diverse ethnicity. The specter of the transcendental subject is still present, no doubt – Shah Jahan the Mughal emperor of the past, the British emperor of the present is also the nation-state of the future – but related to retrospective memory of the inevitable downfall, he is also the commoner, the artist as fragmented subject, co-constituted by the intersubjective community of art production, opening up the possibilities of an alternate nationalism.

The message of diverse ethnicity/religion in ‘The Building of the Taj’ is also not to be missed, and opens up the multivocality of address in this series. Here what is brought to mind and foregrounded is Havell’s cultural Aryanization of the Mughal and his statement “The Taj Mahal belongs to India, not to Islam.” Abanindranath’s engagement with Havell’s text confronts the issue of inclusivism. Are the Mughals to be considered ‘Indian’ because they have ‘accepted’ Aryan cultural values and thus identified themselves as Aryan or is their ‘Indian-ness” based on an intersubjective immersion and acceptance through practice of the diverse lived histories of the subcontinent? Abanindranath’s answer would seem to point to the second option – Shah Jahan, son of Jahangir and grandson of Akbar was born of a Mughal father and a Hindu mother, just as was his father. He is constituted physically and culturally of Hindu and Muslim parts, just as Abanindranth, the Pirali Brahmin is and the historical constitution of the present Indian subcontinent is. This intimate hybridity is reflected in the cultural expression of Shah Jahan. Abanindranathn is undoubtedly drawing from Havell’s statement about the Taj here – according to Havell, the Taj combines Hindu, Islamic and Italian renaissance elements: its unconventional bulbous dome is shaped in the image the lotus bud, its compact faceted cuboid structure influenced by the pancayatana shrine complexes of Hinduism, its minarets, arches, pavilions, calligraphy and other architectural elements drawn from Islamic architectural practice and its pietra dura ornamentation taken from Renaissance Italy.[16] Havell also spells out the Hindu and Muslim co-creation of the project – the architect, Ustad Shah Isa of Turkey was paid Rs. 2000 per month, just as much as were the Hindu pietra dura craftsmen from Kanauj.[17] Though these records are considered questionable today, they undoubtedly background the figures of the architect and craftsman, identified respectively as Muslim and Hindu by their costumes in Abanindranath’s painting. It is this synthesis of elements and cultural traditions that causes Havell to make his pronouncement; “The Taj Mahal belongs to India not to Islam.” Since Havell was clearly interested in the construction of an Indian art history which essentialized a cultural Aryanism, he is certainly open to the charge of inclusivism here. Abanindranath’s visual echo of Havell’s proclamation regarding the Taj has other subjective connotations. Though nominally a Gaudiya Vaishnav, Abanindranath, like his uncle Rabindranath and several others of the Jorasanko community with their Pirali heterodoxy, saw religion, like nation, not as an institutionalized changeless system of belief and practice but as something open to perpetual transformation through lived interpretation and creative mysticism. The “intimate hybridity” of the Mughals could lend itself conspicuously to such transformations. Shah Jahan’s grandfather, Akbar’s religious eclecticism as also Shah Jahan’s eldest son, Dara Shukoh’s serious cross-religious scholarship and practice come to memory, when we read the ‘Building of the Taj’ keeping in mind Abanindranth’s own engagement with religion as a heterodox practice of mysticism in the modern period. The charge of ‘inclusivism’ could not apply here, since the concept assumes institutionally defined religions, for which Abanindranath had little sympathy. The painting thus implies a culture of communitarian or ‘organic hybridity’ (Bakhtin) which either evades and exists in spite of the state or is actively promoted by it. To the British emperor as the British viewer at the Durbar, this message of hybridity, in the person of Shah Jahan and the culture of his kingdom posts an oblique commentary. It defines the last imperial formation, though of ‘foreign’ origin, as “Indian” based on its immersion in the lived histories of the nation, an intimate cultural hybridity, dialogic and intersubjective. It holds up this spectral mirror to the present imperial formation, also of foreign origin, but exempt from national identity by its cultural alienation – or is it alternately a challenge/ invitation to the British emperor and his advisors to enter like the heterodox constituents of Jorasanko into a project of creative and mutually transformative cultural hermeneutics and earn thereby the right to be called “Indian”?

The series, of course, speaks not only to the British viewer but also to the Indian. Here, too, the idea of national belonging is defined in terms of creativity, intersubjective hybridity and eschewal of orthodoxy. Opposing a majoritarian Hindu nationalism which can find no place in its history for Islam, locating the Muslim without exception as foreign invader, it grants national identity on the basis of intimate hermeneutic engagement with the habitus of the nation. Such an engagement, as in the case both of the Mughals and the Jorasanko Tagores, is dynamic and mutually transformative, rather than being invested in ahistorical essences. The ‘Imprisonment of Bahadur Shah’, viewed in Delhi, would provoke the memory of a half-century of subjection to the British throne in Indians, since it was 1856 when in this very city, Hindu and Muslim sepoys united to stand behind the last Mughal badshah and reject British hegemony but were humiliated, while now in the same city the king of England was ironically being proclaimed the emperor of India. Similarly, in the ‘Building of the Taj’ it was Hindu and Muslim together, under the sponsorship and guidance of Shah Jahan, carrying in his person the aura of the rich cross-cultural and cross-religious creativity spawned by Akbar, who engaged in building the hybrid national monument of secular spirituality, the transcendental mysticism of human love. And the “Last Days of Shah Jahan”, for the Indian, would signify not merely the end of pre-British India, but more specifically, the end of the era of tolerance and creative hermeneutic exchange and syncretism/hybrid mysticism between Hindu and Muslim, since these last days were lived in the invisible shadow of Aurangzeb, scourge of Hindus and champion of Muslim orthodoxy. It would portend a future of cruelty and oppression in the name of institutional orthodoxies and ideologies, Islamic fundamentalism under Aurangzeb, civilizational bigotry under the British, the rumblings of Hindu nationalism with the soon-to-come partition of Bengal (1905) and the beginnings of the two-nation theory (Simla Deputation, 1906). Thus, as with its signification to the British, the nostalgia of the last days of Shah Jahan could translate into a yearning for a future where the new Indian nation would be born based on a return to a cultural intersubjective creativity as in a new non-hierarchic version of the ‘Building of the Taj.’ This address to the Indian at large as the constituent of the nation would apply in a more specific way also to the regional viewer of Bengal and its urban center, Calcutta, most well established site of colonial and bhadralok activity. Bengal, as a state, had a large Muslim population and stood, in 1901, on the threshold of political activism. The Mughal/Shah Jahan series was no doubt meant to be a statement of Abanindranath’s orientation in this impending maelstrom, his call to a participatory co-creation of the region, against the exploitative policies of the British.

And finally, the series was addressed in an intimate way to the Jorasanko family community, presenting at this level the issue of hybridity, community and creativity. That this address was coded into the series and not accidental is attested to by the disclosure made by Abanindranath regarding ‘The Last Days of Shah Jahan’. The painting was done, he tells us, after the death of a daughter in the Calcutta plague of 1900 and the sorrow of this loss is what he brought to bear on the painting.[18] We have once more a drawing into the intimate lived community of the act of creation, amplifying the homologous element of the allegory in the paintings – Shah Jahan has commissioned and built the Taj as a result of the mourning of the loss of his wife and Jahanara, his daughter, mourns the passing of Shah Jahan. At the individual level this becomes an allegory of the affective life and its power to put one into contact with an orientation towards death as the condition for authenticity. At the communitarian level of the Jorasanko family then, the series comes to mean something quite different – the passing of the lost glory of India or of a collective life of tolerance and creative hybridity or of a pre-modern age come to take on lived meaning in the mortality of time experienced through the affective life, and its challenge to the creative resources of the community to express that which can transcend this mortality. The hybridity of Shah Jahan and his creation is not lost here either – the individual artist and the communitarian collective, even in their autonomy are not sovereign – they are representatives of the diversity of discourses and histories flowing through the nation and region and their intersubjective creation is made in the name of this hybrid diversity. Creativity illumines, engages and transcends difference so that the creation remains a signpost to dialogic understanding and the bridging of multiple dualities under the banner of the primary duality of human death and immortality. An Orientalist and nationalist project thus translates itself into existential terms and finds a home, a practice and a meaning within the affective play of autonomy and immersion at the lived level of the community.

[1] Inden, Ronald, Imagining India, [], p. 229.

[2] Havell, E.B., History of Aryan Rule in India, New York, pp. 492-538.

[3] Havell, E.B., Indian Architecture, London, 1927, p.24.

[4] Hacker, Paul, “Inclusivism” in Incusivismus, Eine indische Denkform, ed. G. Oberhammer, Vienna 1983, pp. 11-28, referenced in Halbfass, Wilhelm, Indian and Europe: An Essay in Philosophical Understanding, Motilal Banarasidas, New Delhi, 1990, p. 403.

[5] Banerji, Debashish, “The Orientalism of E.B. Havell”, Third Text, Vol. 16, Issue 1, 2002, pp. 53-6.

[6] Tagore, Abanindranath, Jorasankor Dhare, pp. 240, 306-7. Abanindranath reminisces about two different instances of the plague which made the family move out of Jorasanko to rented quarters in Chowringhee, the “white part” of town. The first instance, coupled with an earthquake, seems to point to 1896. This move saw the death of Gaganendranath’s eldest son. The second visit, following the plague which killed Abanindranath’s daughter, seems to have been in 1900. Though he remembers this second move as the time when he first met Havell at the home of Gyananandini Debi, this is unlikely, since he was already well acquainted with Havell by 1900. Thus, it is more likely that he met Havell for the first time in 1896 or 1897.

[7] Havell, E.B., The Studio, vol. 44, 1908, p.111.

[8] Tagore, Abanindranath, Jorasankor Dhare, [], pp. 157-8.

[9] Ibid, , p. 101.

[10] Mitter, Partha, Op. cit, p. 299

[11] R. Siva Kumar, “Abanindranath’s Paintings Based on the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam” in Lavanya: A Journal of the Chandigarh Lalit Kala Akademi, Vol 1, No. 3, August 1995, p. 21

[12] Mitter, op. cit, p. 288.

[13] Mitter, op. cit., p. 285, 287.

[14] Panikkar, Shivaji K, Nair, Preetha and Das Gupta, Anshuman, “Art, Subjectivity and Ideology: Colonial and Post-Independent India” in Nandan, Vol XVII-1997, Kala Bhavan, Shantiniketan, 1997, p. 28

[15] Mitter, Partha, Art and Nationalism in Colonial India, 288.

[16] Havell, , Indian Architecture, London, 1927, p. 24-7, 84.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Tagore, Abanindranath, Jorasankor Dhare, [], p. 306-7.